ABSTRACT

Regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) have emerged as a promising approach to treat immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis by promoting pulp regeneration and root maturation. Nevertheless, the selection of an optimal scaffold remains a critical challenge. Collagen scaffolds, noted for their biocompatibility and bioactivity, have garnered considerable increasing attention in the field of dental pulp tissue engineering. However, most commercially available collagen products currently employed in REPs originate from non-pulp environments, raising concerns about their appropriateness for REPs. Thus, we review the recent advancements in applying collagen-based scaffolds within REPs. Clinically, their use is associated with high survival rates and yield favorable outcomes of tooth after REPs, such as pulp vitality recovery, dentin wall thickening and apical closure in necrotic immature permanent teeth, though root lengthening remains less consistently achieved. Histologically, the newly formed mineralized tissue from collagen-based scaffolds within REPs tends to cementum or bonelike tissue rather than reparative dentin. To advance the genuine pulp-dentin regeneration, we further discuss how their intrinsic physicochemical properties of collagen scaffolds influence regenerative outcomes, including pore size, porosity, concentration, stiffness, viscosity and viscoelastic properties. Additionally, we introduce innovative tissue engineering strategies to optimize collagen scaffolds for enhanced clinical performance in the future applications on REPs. In conclusion, this review is expected to significantly advance the development of collagen scaffolds in REPs and facilitate their future clinical translation.

Keywords: Regenerative endodontic procedures; collagen scaffold; pulp-dentin complex; tissue engineering; clinical outcomes; histological characteristics

INTRODUCTION

According to data from the World Health Organization databank covering the years 2000 to 2015, dental caries affects between 21% and 97.3% of children aged 5 to 12 years [1], often resulting in pulpal injury and necrosis [2]. The conventional management of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis and apical periodontitis involves apexification and apical barrier techniques [3]. However, these methods do not succeed in restoring physiological pulpal function or facilitating root maturation.

Recently, regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) have emerged as a contemporary alternative, aiming to promote pulp regeneration and root maturation [4]. Progress in REPs has been driven by tissue engineering strategies that facilitate targeted therapeutic interventions [5]. The rational combination of biomaterials can create optimized microenvironments that are conducive to regeneration, thereby supporting functional reconstruction through the use of growth factors and scaffold design [6]. Nevertheless, selecting an appropriate scaffold remains a significant challenge, as essential cellular processes such as migration, proliferation, and differentiation are profoundly influenced by the properties of the materials used [7].

Extensive investigation into scaffolds for REPs has identified blood clots (BCs), collagen, and autologous platelet concentrates (APCs), as leading candidates [8]. Therein, collagen, as the primary component of dental pulp, exhibits viscoelastic properties akin to those of native pulp tissue [9], thereby garnering increasing interest in pulp tissue engineering applications [4-5,10]. In 2008, Jung et al. were among the pioneers in utilizing collagen matrices in REPs to promote new tissue formation within the pulp chamber, particularly when inadequate bleeding hinders natural clot formation [11]. Subsequently, a growing number of studies have employed collagen as a carrier for stem cells and growth factors, highlighting its favorable biocompatibility and potential to facilitate tissue regeneration in dental pulp [12-15]. A significant advantage of collagen in REPs is its established application in human medicine, with several commercially available products such as CollaPlug®, CollaTape®, Bio-Gide®, SynOssTM Putty and CollaCoteTM produced on a large scale [14-18]. Studies have reported the formation of pulp-like connective tissues from collagen scaffolds in REPs within experimental models [12,19-20]; however, the structural and functional characteristics of these tissues warrant further investigation. What’s more, it must be noted that most commercially available collagen products currently employed in REPs originate from non-pulp environments, raising legitimate concerns about their appropriateness for pulp regeneration.

In this review, we summarize recent advances in the application of collagen based scaffolds for REPs, with a focus on their clinical outcomes and histological evaluations. Considering the current limitations of collagen scaffolds in REPs, we further propose modification strategies aimed at enhancing their regenerative efficacy. We discuss how to optimize the inherent physicochemical properties of collagen that influence pulp regeneration, including pore size, porosity, concentration, stiffness, viscosity and viscoelastic properties. Additionally, we employ the innovative tissue engineering strategies to tailor collagen scaffolds, anticipating to provide innovative insights and solutions for achieving effective regeneration in REPs.

Clinical Application Outcomes of Collagen Scaffolds in REPs

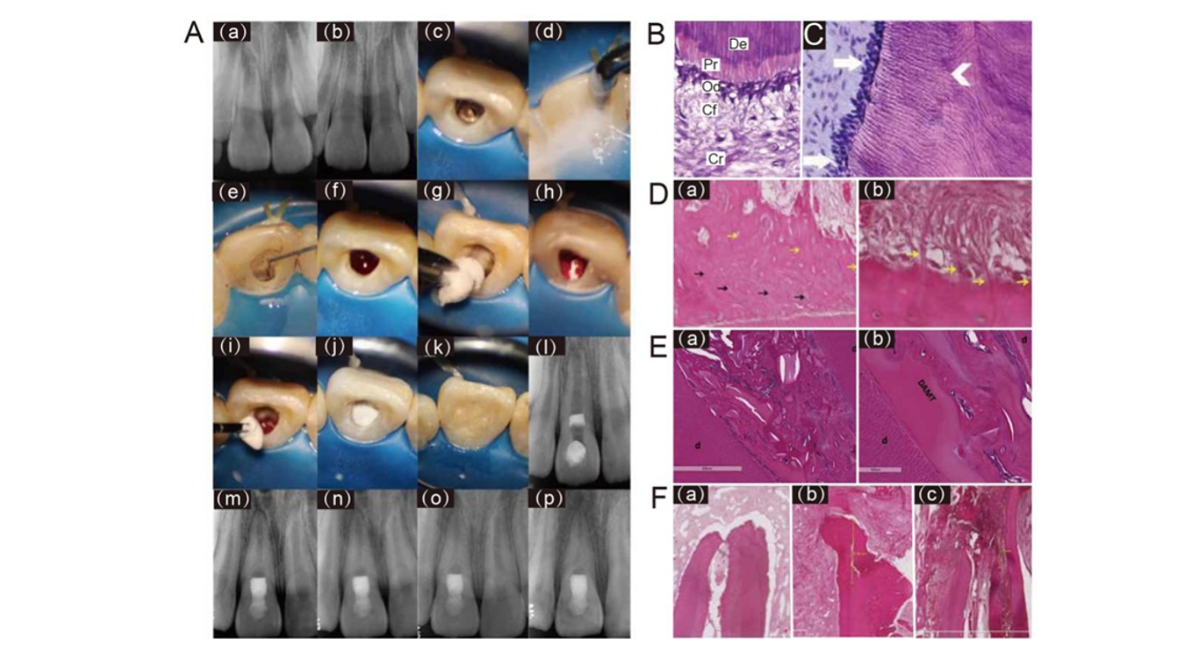

Since the introduction of collagen scaffolds within REPs in 2008 [11], clinical applications have largely relied on commercial products, as detailed in Table 1. Numerous clinical studies and systematic reviews have validated the effectiveness of collagen scaffold in REPs, with survival rates ranging from 85% to 100% and success (healed) rates from 80% to 100% over a follow-up period of 23 months [13,15,21-22]. Similarly, for necrotic immature teeth, REPs employing BCs or other scaffold demonstrated survival rates ranging from 95.6% to 100% at least a 12-month follow-up [22-25]. These outcomes indicate that collagen scaffolds yield clinical success rates comparable to those of other scaffold in REPs. Consequently, both the American Association of Endodontists (AAE) and Chinese expert consensus guidelines recommend their use in REPs [26-27], particularly in cases where adequate blood clot formation is compromised (Fig. 1A). Nevertheless, the long-term effectiveness of collagen scaffolds in REPs warrants further validation through more rigorous clinical studies.

The success of REPs is not solely defined by the resolution of clinical signs and the evidence of radiographic healing; it also encompasses the potential to promote continued root development and apical closure. A previous study has highlighted the significant role of collagen scaffolds in promoting the thickening of dentinal walls during REPs [28]. Similarly, Jiang et al. also found that the Bio-Gide® collagen membrane significantly increased dentin wall thickness in the middle third of the root after REPs compared to BCs [29]. An increase in root thickness from 3.0 mm to 5.0 mm enhances fracture resistance by 70% [30]. Thus, these findings underscore the importance of root thickness in improving the mechanical properties of dental structures.

One randomized controlled clinical trial reported that REPs utilizing collagen scaffolds were found to induce apical foramen closure in 47% of teeth; this process began as early as 6 months postoperatively, with closure achieved in the vast majority (96%) of cases by 24 months [22]. Interestingly, another study suggested that platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) might possess superior regenerative capacity compared to collagen scaffolds, as evidenced by increased apical closure, dentin thickness, and root lengthening [31], potentially due to its higher concentration of growth factors. However, a meta-analysis concluded that no significant difference exists among BCs and other exogenous scaffolds in terms of root development outcomes [32], implying that the advantage of collagen scaffolds could be specific to enhancing dentin wall thickness [14, 22]. Key prognostic factors such as the tooth's developmental stage, follow-up duration, and disease etiology significantly influence the outcome of root development [15, 33]. According to the clinical considerations for REPs revised by AAE in 2023 [26], an increase in the thickness of the root canal walls is typically observed 12 to 24 months following treatment. However, it is worth noting that the study, with a maximum follow-up of only 12 months, might be insufficient to fully capture this outcome [31]. Consequently, the long-term stability and potential changes in outcomes over an extended period remain an open question.

Regarding the pulp vitality recovery after REPs, the rate of positive responses to the cold test and/or electric pulp testing (EPT) on necrotic immature permanent teeth ranges from 14.5% to 33.3% [25, 34]. For REPs utilizing collagen scaffolds in such teeth, the reported positive response rate ranges from 32% to 55%, observed as early as 3 months postoperatively [35], with the majority occurring within 24 months [13, 15, 22]. These findings suggest that the use of collagen scaffolds within REPs may be associated with a higher rate of pulp vitality recovery, which aligns with the results reported by Jiang et al [22]. In contrast, several studies using collagen matrices in REPs for immature permanent teeth reported no pulp sensibility responses throughout the follow-up period [36-38]. Several factors may explain these negative outcomes [39]: 1) the inherent difficulty in obtaining reliable pulp testing scores in pediatric patients; 2) potential interference from a thick, multilayered coronal seal placed over the scaffold; and 3) the absence of well-organized dentin tubules in newly regenerated and mineralized root canal tissues. Unlike natural dentin, where sensitivity is mediated by hydrodynamic activity associated with A-β sensory fibers [40], the regenerated tissue lacks this structural basis for normal sensitivity. Thus, the aforementioned hypotheses may collectively account for the generally lower rate of positive sensitivity responses observed in REPs, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation of pulp sensibility test results in this context.

Root canal calcification is a frequently reported complication following REPs, and its incidence ranges from 30.7% to 62.1% with an average follow-up period of 12 to 24 months [14, 41-44]. For REPs utilizing collagen scaffolds, Lin et al. reported that the calcification rate was 37.6%, with most cases detected at the 6-month recall [45]. Despite extended follow-up durations ranging from 15 to 33 months, the calcification rate remained stable at approximately 47% in REPs with collagen scaffolds [22], indicating that not all treated teeth develop calcification, even with follow-ups as long as 78 months [14]. However, Jiang et al. found no significant correlation between root canal calcification and factors such as tooth type, etiology, preoperative diagnosis, apical lesion status, initial root development stage, intracanal bleeding quality, or scaffold type [14]. It is noteworthy that induced apical bleeding—a procedural step common to most REPs prior to the placement of PRF, collagen, or other scaffolds—may introduce periodontal and bone marrow-derived stem cells into the root canal space [46]. Biological evidence suggests that these cells can promote the formation of bone- or cementum-like mineralized tissues in the canal space [46]. Therefore, while scaffold type was not identified as a correlative factor, the potential contribution of the initial BCs to calcification cannot be entirely excluded and merits further validation in prospective studies.

In summary, despite the fact that most commercially available collagen products are mainly applied in non-pulp environments (Table 1), their use in REPs have demonstrated considerable promise, achieved high survival/success rates and pulp vitality recovery, as well as promoting dentinal wall thickening and apical closure in necrotic immature teeth. However, some researchers concerned that the limitations such as rapid degradation and low mechanical strength may affect the performance of collagen-based scaffolds in REPs [47]. Several histological studies of REPs with collagen scaffold on human teeth have reported no detectable collagen residues as early as 5.5 months post-treatment [48-50]. In cases using SynOss™ Putty a composite containing both collagen and hydroxyapatite histologic sections revealed residual scaffold particles at 7.5 months after REPs, though without evidence of remaining collagenous material [51]. While the precise timeline from initiation to complete degradation of collagen scaffold remains unclear from the currently reported clinical cases in REPs, no available studies have indicated that collagen degrades too rapidly, suggesting that the degradation rate of current commercial collagen-based scaffolds is adequate for REPs. Similarly, none of the clinical studies or cases reported failures attributable to poor mechanical properties, indicating that the mechanical performance of existing commercial collagen scaffolds appears sufficient for REPs a view consistent with that of Moussa et al [52]. Theekaku et al. reported a failure rate of 10% (13/120 teeth) in REPs with using collagen, with primary causes including persistent infection, coronal and/or root fracture, and postoperative secondary trauma15. Thus, future efforts should focus on developing multi-functionally enhanced collagen composites that improve anti-bacterial abilities, coupled with prospective long-term clinical studies to validate sensory recovery and minimize mineralization risks [53].

|

Brand Name |

Character |

Main Composition |

Source |

Main Uses in Dentistry |

Clinical Outcomes in REPs |

|

CollaPlug® |

Collagen |

High-purity Type I collagen |

Bovine |

Hemostasis, oral wound protection and repair, and small bone defect |

Radiographic periapical |

|

CollaCote™ |

Collagen |

High-purity Type I |

Bovine |

Hemostasis, oral wound |

Radiographic periapical |

|

CollaTape® |

Collagen |

High-purity Type I |

Bovine |

GTR, oral wound repair |

Radiographic periapical |

|

Bio-Gide® |

Bilayer |

Cross-linked Type |

Porcine |

GTR, GBR |

Radiographic periapical |

|

SynOss™ |

Bone graft |

Type I collagen and |

Bovine |

REPs, GBR and |

Radiographic periapical |

Table 1: Commercially available collagen products applied in REPs

Abbreviations: GTR: guided tissue regeneration; GBR: guided bone regeneration; REPs: regenerative endodontic procedures

Characteristics of the Formed Mineralized Tissue in REPs with Collagen Scaffolds

The properties and quantity of mineralized tissue within the root canal are closely related to the prognosis of REPs.Although clinical and imaging studies have demonstrated favorable outcomes of REPs utilizing collagen scaffolds, the structural and functional characteristics of the newly formed mineralized tissue in the root canal warrant further investigations.

Based on the formation mechanisms, the newly formed mineralized tissues in the root canal after REPs can be primarily classified into four types: reparative dentin, cementum-like tissue, bone- like tissue, and periapical hard tissue [54] (Fig. 1C-F). Currently, the predominant mineralized tissues observed in the root canal following REPs are cementum-like tissue and bone-like tissue [54-55], suggesting that the microenvironment within the root canal post-surgery is more favorable for the differentiation and proliferation of periodontal ligament mesenchymal stem cells [48, 56].

Cementum-like tissue, also known as dentin-associated mineralized tissue (DAMT), is formed through the differentiation of stem cells within the periapical tissues, following the apical blood supply [57-58]. DAMT manifests as mineralized tissue with a relatively uniform thickness, which may or may not contain embedded cells within the mineralized matrix (Fig. 1D). The boundary between cementum-like tissue and canal dentin can be clearly identified by the absence of dentinal tubules in the former55. The bond between DAMT and the dentin wall is not particularly robust; certain regions are detached from the wall, while others are anchored to the dentin wall via Sharpey's fiber- like tissue20, [48,55] (Fig. 1D-b). Longitudinal sections of teeth treated with CollaPlug® after REPs demonstrated that the newly formed mineralized tissue on the canal walls comprised both cellular and acellular cementum-like tissue, as well as bone-like tissue [48]. Furthermore, the canal dentin appeared to connect directly to the cementum-like tissue, with collagen bundles inserted into both the cementum-like and bone-like tissue at right angles, resembling Sharpey’s fibers [48]. Some researchers have proposed that specific demineralization treatments of dentin, such as increased ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) irrigation, could create a hair-like protrusion structure on the dentin surface, thereby enhancing the attachment strength of newly mineralized tissue to the root walls [54-55]. Additionally, other researchers have indicated that DAMT continues to deposit over time until the root canal is completely sealed [59]. However, the relatively short follow-up periods in both animal and clinical studies conducted thus far provide insufficient evidence to conclusively validate this assertion. Elnawam et al. have found that in the REPs for necrotic mature canine teeth, cementum-like tissue deposition was detected on internal canal walls of most samples in the BCs group and bovine dental pulp derived extracellular matrix (P-ECM) hydrogels group [19]. However, intracanal hard tissue detected was significantly higher in the BCs groups compared to the P-ECM group [19]. Similarly, another study also established a model of REPs for necrotic mature canine teeth and found that, there was no regenerated mineralized tissue on the root canal dentin in most roots in the BCs and CollaPlug® groups and all roots of the amnion-chorion membrane (ACM) group, although the amount of regenerated fibrous tissue and the perfused blood vessels in the root canals was greater in the membrane groups than in the BCs group [20]. This might be due to the retained growth factors and ECM components within the collagen scaffold that could influence the chemotaxis and commitment of surrounding stem cells [60].

Unlike DAMT, bone-like tissue, also referred to as bony islands (BI), is situated within the inner lumen, independent of the dentin wall [54]. These tissue manifests as islands of mineralized matrix that harbor numerous embedded cells, blood vessels, and bone marrow-like tissues [55] (Fig. 1E). A histological study revealed that bone-like tissue comprised osteocyte-like and osteoblast-like cells, which contributed to the formation of mineralized tissue islands within the central portion of the canal space [48]. In certain specimens, it was observed that BI potentially originated from the bone marrow in the periapical area 61(Fig. 1F-c) and occasionally appeared to connect with DAMT [51] (Fig. 1E-a). Additionally, several areas of fusion and calciotraumatic lines could be observed between BI and DAMT51 (Fig. 1E-b). Another case exhibited periodontal ligament (PDL)-like tissue, albeit very loose, located between the BI and the DAMT, resembling the naturally occurring structure on the outer root wall [19]. It is conceivable that PDL cells migrating along the dentin walls and cells from the bone marrow compete for space within the root canal lumen, with different cell types potentially being directed towards their preferred microenvironments to form their respective tissues.

According to the three-level outcome criteria for REPs established by the AAE, some researchers have proposed that, considering the current immaturity of REPs techniques, the presence of cementum-like tissue within the root canal could already satisfy the first and second-level criteria and achieve a favorable prognosis [45]. Literature indicate that the prognosis of cementum-like tissue is superior to that of bone-like tissue [62]. However, the most desirable outcome remains the formation of reparative dentin [54]. Studies indicate that collagen scaffolds could promote the formation of reparative dentin (Fig. 1C). Abdelsalam et al. found that, compared to the BCs group, the BCs and collagen group exhibited clearly defined distinct cellular elements and new dentin formation at the pulpal side of the root dentin [12]. Furthermore, decellularized extracellular matrix from the periapical lesion (PL-dECM), along with periapical lesion-derived stem cells (PLDSCs), was implanted into the subcutaneous area of nude mice, resulting in an ideal pulp-like matrix characterized by a relatively dense eosin-stained matrix with numerous ordered nuclei and a predentin-like structure adjacent to the tooth section [63]. Immunohistochemical staining further demonstrated that PLDSCs within PL-dECM exhibited higher protein expression levels of dentin Sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [63]. Another study employing both hematoxylin-eosin staining and immunostaining revealed that the neotissues formed represented dentin-like tissue in teeth treated with CollaPlug® in REPs [49]. The newly formed dentin appeared organized and tubular, representing a primary dentin phenotype. Moreover, the newly formed dentin was continuous with native dentin and was lined with mature, secretory odontoblast-like cells [49]. This finding is unique and novel, as previous studies investigating the nature of neotissues observed a reparative dentin phenotype that differs from native dentin in terms of volume and density [64-65].

Besides, it is interesting that only collagen scaffolds do not appear to promote pulp regeneration. A study indicated that the use of SynOssTM Putty without blood resulted in the formation of periapical lesions without any tissue regeneration in human immature teeth [51]. Furthermore, this study investigated the efficacy of collagen scaffolds with varying degrees of blood draw [51]. In teeth treated with SynOssTM Putty and blood, histological examination revealed the formation of intracanal mineralized tissue around the scaffold particles, which solidified with newly formed cementum-like tissue on the dentinal walls. In contrast, teeth treated with SynOssTM Putty and minimal bleeding (limited to the apical third) exhibited newly formed tissues only in the apical area, and the remaining root canal spaces were filled with disintegrating SynOssTM Putty particles. These results suggest that collagen scaffolds within REPs necessitate the accompaniment of apex blood draw to promote pulp regeneration. Platelets in BCs contain and secrete active growth factors and a variety of serum proteins, including fibrin, fibronectin, and vitronectin, which serve as cell adhesion molecules for odontoblastic differentiation. Additionally, compared to peripheral blood, blood from periapical tissues contains a significantly higher concentration of mesenchymal stem cell markers, with an increase of up to 600 times [66]. Thus, blood plays a crucial role in the formation of new tissue within the root canal space.

For the changes to the periapical and periodontal tissues, histological studies have indicated that the apical development appeared to be an extension or growth of the cementum/DAMT structure [12, 51, 55] (Fig. 1F), facilitating apex closure or the reconstruction of normal apex anatomy. This newly formed tissue is continuous with the PDL at the apex, where the scaffold material is absent [12, 48, 51]. Additionally, PDL-like fibers are inserted into the cementum-like and bone-like tissue at right angles as Sharpey’s fibers [48]. Evidence from a study demonstrated the presence of cementocytes within the apical apertures and apical closure with cementum-like tissue in the BCs and collagen group. In contrast, the BCs group exhibited sporadic degenerative alterations alongside heavily pigmented basophilic condensation of fibrous tissues [12]. The inability to achieve complete sealing of the apex is frequently associated with BI55, [67] (Fig. 1F-c), and the presence of BI may contribute to the higher failure rate of REPs compared to apexification in immature permanent teeth [45].

In summary, the formation of reparative dentin predominantly takes place in the middle third of the root, whereas the apical region is frequently characterized by cementum-like and bone-like tissues. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that the fate of recruited stem cells is contingent upon the regenerative cues present in the vicinity of the attached cells, which promote differentiation into specific cell lineages. In the investigation of collagen scaffolds that promote reparative dentin formation, the odontoblastic differentiation of the attached stem cells is likely influenced by both spatial cues from the dentin surface and biological signals emanating from the collagen scaffold. However, although clinical and imaging studies have demonstrated favorable outcomes, histological investigations of REPs with collagen scaffold have indicated a process of repair rather than regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex.

Figure 1: Clinical diagram and histological evaluation of regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) using collagen scaffold.

(A) REPs performed with a pure collagen scaffold for an immature tooth 8 with intrusive luxation and diagnosed as symptomatic apical periodontitis approximately 4 months after injury. The tooth showed continued root canal space narrowing 48 months after treatment. (a-b) Periapical radiographs of tooth 8 after injury and 4-month post-injury. (c–e) Clinical image of tooth 8 involved access opening, irrigation, and medication of the root canal. (f) Clinical image of inducing apical bleeding into the canal space. (g–h) Clinical image of placing a piece of resorbable collagen sponge over the blood clot. (i–j) Clinical image of incrementally placing a 3- mm thick layer of bioceramic paste over the collagen sponge. (k) Clinical image of filling the access cavity with resin composite. (l-p) Periapical radiographs of tooth 8 after treatment, 6-month, 12- month, 24-month and 48-month follow-up. Reprinted with permission from Ref [4] (B) HE staining of the dentin-pulp interface in a healthy tooth. Dentin (De) with tubules running parallel to each other; predentin (Pr) with uniform thickness; palisading odontoblast layer (Od); cell-free zone (Cf); cell-rich zone (Cr) (original magnification x400). Reprinted with permission from Ref [68] (C) Reparative dentin. Mature, secretory odontoblasts lining newly formed tubular dentin (arrows). Reprinted with permission from Ref [49] (D) Cementum-like tissue. (a) deep layer of acellular cementum-like tissue (black arrows) covered by cellular cementum-like tissue (yellow arrows). (b) Sharpey’sfibres-like projections inserted into a cementum-like layer (yellow arrows). Reprinted with permission from Ref [61]. (E) bone-like tissue. (a) The newly formed intracanal mineralized tissue that is transitioning toward full calcification is intermixed with scaffold particles and connective tissue. (b) The areas of solidification between dentinal walls, DAMT, and the newlyformed intracanal mineralized tissue with calciotraumatic lines in between. Reprinted with permission from Ref [51] (F) periapical hard tissue. (a-b) The apical foramen was sealed by cementum-like tissue; (c) the apical foramen was closed by bone-like tissue. Reprinted with permission from Ref [61].

Physicochemical Properties of Collagen Modulating the Formation of the Pulp-Dentin Complex

The proliferation and differentiation of stem cells (such as dental pulp stem cells, DPSCs) within a specific microenvironment serve as an indispensable link in the formation of the pulpal- dentin complex [69-70]. Understanding the relevant physicochemical properties of biomaterials is crucial for optimizing the survival microenvironment of stem cells, thereby maximizing the efficacy of cell-based therapies. Collagen scaffolds, primarily composed of type I collagen, are regarded as effective substitutes for the extracellular matrix (ECM) due to their porous physicochemical structure and preserved sequences capable of binding to specific cell recognition sites, such as the RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) sequence [70-71]. During dental pulp regeneration, integrins on stem cells mediate cell-collagen adhesion to form focal adhesions, which subsequently connect with the intracellular cytoskeletal protein vinculin to establish a mechanism capable of transmitting mechanochemical signals across the cell membrane through conformational changes. This establishes a dynamic linkage capable of sensing microenvironmental rigidity variations and modulating the expression of stem cell markers [72]. Meanwhile, the porous physicochemical structure of collagen scaffolds provides essential spatial accommodation for stem cell adhesion and proliferation [71-72]. Collagen scaffolds are considered promising carriers for stem cells and growth factors in dental pulp regeneration, demonstrating favorable biocompatibility and regenerative potential that hold significant promise for future applications [73-76]. Nevertheless, the influence of their intrinsic physicochemical properties on regenerative outcomes remains insufficiently elucidated, necessitating further investigation to inform standardized design and clinical translation.

Pore size is often the primary consideration among various physicochemical parameters due to its direct influence on cell infiltration, nutrient diffusion, and vascularization. Multiple investigative groups have consistently reported superior regenerative outcomes where pore size was maintained within an optimal window of 60–90 µm, particularly for mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with an average diameter of 30 µm [77]. For instance, Qianli Zhang et al. prepared collagen scaffolds with varying average pore sizes (approximately 20 µm, 65 µm, and 145 µm) and demonstrated that the group of 65 µm induced the highest levels of odontogenic-related gene (DSPP, DMP-1) and protein (DMP-1) expression in human dental pulp cells (hDPCs), simultaneously promoting mineralization and vascularized tissue formation [78]. Similarly, HengamehBakhtiar et al. reported that ECM scaffolds with a pore size of 7804 ± 16 µm exhibited superior physicochemical properties, with higher mineralization nodule formation and calcium deposition compared to other pore size groups, and more significantly supported the migration behavior of human dental pulp stem cells (hDPSCs) [79]. Furthermore, the porosity of collagen scaffolds is critical for achieving pulp regeneration, highlighting its significance in scaffold-based pulp regeneration strategies. Generally, higher porosity facilitates vascularization and nutrient transport. However, excessively high porosity often significantly reduces the mechanical strength of collagen scaffolds, potentially failing to maintain the stability of the pulp cavity structure and thus hindering pulp regeneration. Currently, collagen scaffolds used in pulp therapy typically have a porosity controlled at around 95.6% [80].

The pivotal role of collagen scaffold concentration in steering the regenerative process toward functional dentin-pulp complex formation has been well-documented. An in vitro study revealed that at concentrations below 1%, collagen scaffolds exhibited severe contraction (up to 40%); increasing to 2% markedly reduced shrinkage while enhancing both cellular distribution and odontogenic differentiation within simulated root canals. Nevertheless, an increase in concentration up to 3% limits the capacities of cells for migration and proliferation, which adversely affects their survival [81]. Another study by Hengameh Bakhtiar et al. reported that decellularized human amniotic membrane (HAM) scaffolds at 3.00 mg/ml displayed enhanced degradation and significantly promoted the migration of hDPSCs compared to lower-concentration variants [79]. Subsequent animal studies demonstrated that lyophilized ECM scaffolds at a concentration of 3.00 mg/ml exhibited optimal performance, showing the highest viability and proliferation rates of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMMSCs) along with marked upregulation of dentinogenic markers such as DMP-1 and collagen I [82]. However, no consensus has been reached regarding a well-defined optimal concentration range, underscoring the need for further systematic investigation. This discrepancy could be due to differences in the evaluation criteria established for the experiments, or alternatively, to the influence of other physicochemical properties of the collagen scaffold.

As a key microenvironmental cue, the stiffness of collagen scaffolds is known to modulate the lineage commitment and differentiation fate of MSCs. One research team engineered two distinct collagen hydrogels with contrasting stiffness profiles a soft formulation (Col³, 735 Pa) and a rigid one (Col¹⁰ , 8,142 Pa). The softer hydrogel preferentially directed DPSCs toward an endothelial lineage, as evidenced by upregulated expression of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and CD31. In contrast, the stiffer matrix enhanced odontogenic differentiation, marked by elevated levels of DSPP and RUNX2 [83]. These values strategically approximate the mechanical properties of native pulp (500–1,000 Pa) and predentin (5,000–10,000 Pa), respectively, supporting the concept that biomimetic physicochemical cues can guide stem cell fate toward specific tissue regeneration pathways [83].

The viscosity of collagen scaffolds represents a critical design parameter for clinical translation in pulp regenerative therapy. A comparative in vitro study by V. Rosa et al. revealed significant temporal differences in odontogenic differentiation when stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) were cultured in Puramatrix™ versus recombinant human type I collagen (rhCollagen): the Puramatrix™ group exhibited odontoblast markers within 7 days, while the rhCollagen group required 14 days, which attributed to rhCollagen's higher viscosity potentially hindering SHED migration and delaying the diffusion of dentin-derived morphogenetic signals [84]. These findings directly inform scaffold design strategies: optimizing viscosity parameters can enhance cell motility and accelerate bioactive signal propagation.

Collagens from different sources exert varying effects on pulp regeneration due to differences in their structure, purity, and bioactivity. Currently, collagens applied in dental pulp regeneration are primarily derived from bovine or porcine skin and tendon tissues. These naturally sourced collagens retain intact spatial structures and biological information, providing a highly biomimetic microenvironment for cells [85]. The advantages of animal-derived collagens lie in their mature extraction processes and relatively low cost. However, significant differences exist in antigenicity and biocompatibility among collagens from different species. Bovine-derived collagens (such as commercial products like CollaPlug® and CollaTape®) are the most widely used in dental pulp revascularization procedures, while porcine-derived collagens have garnered attention due to their higher structural similarity to human collagen. At the molecular level, the differences among collagens from various sources are primarily reflected in their capacity as cellular information carriers. Studies have demonstrated that mammalian collagens exhibit significantly stronger binding affinity to integrin α2β1 compared to fish collagens, with hydroxyproline (Hyp) content showing a positive correlation with binding capacity [86]. The GFOGER sequence (Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Glu-Arg) in type I collagen serves as the key motif for specific binding to integrin α2β1 [87]. This binding triggers downstream osteogenesis-related signaling pathways (such as focal adhesion kinase [FAK], mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK], and runt-related transcription factor 2 [RUNX2]), thereby accelerating the osteogenic process. This specific interaction explains the notable differences in the efficacy of dental pulp regeneration observed with collagens from diverse sources. Moreover, the viscoelastic properties of collagen scaffolds are closely related to pulp regeneration (Fig.2). Through experimental measurements and analyses, CevatErisken et al. demonstrated that the dynamic properties of collagen gels, including storage modulus, loss modulus, and tan δ, approximated those of natural pulp tissue, although their compressive properties fell significantly short9. Based on these findings, the study proposed that collagen scaffolds and other regenerative materials should more accurately replicate both the dynamic and compressive properties of natural pulp by modulating gelation agents and their concentrations, in order to enhance regenerative efficacy.

In conclusion, the physicochemical properties of collagen scaffold are essential in modulating the formation of the pulp-dentin complex. An ideal collagen scaffold for pulp regeneration should possess a pore size of approximately 60–90 µm and a porosity of around 95%. Furthermore, studies suggest that mimicking the hardness, viscosity, and viscoelasticity of native dental pulp tissue enhances pulp regeneration, underscoring the importance of "biomimicry of materials" as a critical area for exploration. Additionally, the degradation rate of the scaffold should synchronize with the rate of new pulp tissue formation. However, current research has limitations. On the one hand, the interactions between different physicochemical properties remain unclear. The efficacy of collagen scaffolds in promoting pulp regeneration stems from the synergistic effects of multiple physicochemical properties; thus, a systematic consideration of multiple physicochemical indicators is necessary when evaluating the potential of collagen scaffolds. On the other hand, the optimal concentration range of collagen scaffolds and data on pulp tissue regeneration rates require further investigation. Such research would guide the construction of collagen scaffolds with appropriately synchronized degradation rates, ultimately improving clinical efficacy. Furthermore, to enhance regeneration outcomes, the physicochemical properties of collagen scaffolds can be enhanced through the following approaches to improve pulp regeneration outcomes: 1) optimizing extraction and fabrication processes; 2) modifying collagen scaffolds via surface treatment or chemical functionalization; and 3) incorporating other materials into pure collagen to form composite scaffolds. Ultimately, development in tissue engineering for pulp regeneration has garnered increasing attention. By utilizing collagen scaffolds as carrier vehicles, this approach holds significant promise for transcending the inherent limitations of the scaffolds themselves

Figure 2: Schematic diagram illustrating the physicochemical properties (e.g., pore size and porosity, concentration, stiffness, viscosity and different sources) of collagen scaffolds influencing the regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex.

Tissue Engineering Strategies for Precision Regeneration with Collagen Scaffolds

Regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex involves a cascade of biological events, including bioactive molecule activity, stem cell recruitment, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis, that remain difficult to achieve using current REPs [88]. Dental pulp tissue engineering, based on the "cell– scaffold–biomolecule" triad, provides a theoretical and practical framework for shifting from clot- dependent "repair" toward controllable "true regeneration" [89].

Collagen scaffolds function both as reservoirs and sustained-release carriers of bioactive molecules, and as matrices that encapsulate stem cells to enhance pulp regeneration. Studies indicate that incorporating stem cells or biomolecules into collagen scaffolds represents a promising approach to achieve genuine regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex83, [90-91]. A comparative experiment demonstrated that the combined use of hDPSCs, type I collagen scaffolds, and DMP1 significantly promoted differentiation into odontoblast-like cells, collagen matrix deposition, and angiogenesis, compared with collagen-based scaffolds alone [90]. Similarly, another in vivo mouse experiment showed that collagen scaffolds loaded with VEGF and bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) stimulated DPSCs to differentiate into endothelial cells and odontoblasts, and successfully generated blood-perfused vascular networks and mineralized dentin tissue [83]. Further, collagen combined with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and laponite promoted abundant new blood vessel formation and reparative dentin deposition through specifically recruiting and inducing SCAPs to differentiate into odontoblast-like cells [91]. In addition to the biomolecules mentioned above, other critical signaling molecules, including Wnt, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), EctodysplasinA (EDA), Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), and members of the MAPK family, also play crucial roles in dental pulp regeneration [92], and were summarized in Table 2. It is worth nothing that microRNAs exert multiple regulatory roles in dental pulp-dentin regeneration. Future approaches combining collagen scaffolds with stem cells and specific miRNAs such as miR-378 inhibitors or miR-26b/miR-126-3p, may achieve synergistic effects, enabling advanced functional regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex [93].

Stem cells constitute one of the three essential elements in tissue engineering. Cells utilized for pulp regeneration can originate from various odontogenic and non-odontogenic sources. Non- odontogenic sources include embryonic stem cells, neural crest stem cells, BMMSCs, adipose- derived MSCs (AD-MSCs), and umbilical cord MSCs (UC-MSCs) [94]. Odontogenic stem cells, including DPSCs, SHEDs, and stem cells from apical papilla (SCAPs), exhibit multilineage differentiation abilities, making them key candidates for pulp-dentin complex regeneration. DPSCs display typical characteristics of MSCs [95], and demonstrate lower immunogenicity and higher proliferation rates compared with other MSCs, highlighting their potential for regenerative applications [96-97]. Liu et al. recently demonstrated that injection of allogeneic DPSCs significantly promotes periodontal regeneration in a clinical trial, indicating the maturation and clinical relevance of DPSC-based therapies [98]. SCAPs, derived from developing roots, possess robust proliferation and differentiation capacities, facilitating apex closure and root development. Compared with DPSCs,

SCAPs exhibit higher telomerase activity and greater dentinogenic potential [99]. Although SCAPs remain functional in normal or reversibly inflamed pulp tissues, irreversible pulpitis decreases cell viability, and necrosis results in tissue disintegration [68]. Furthermore, study demonstrates that SHEDs are stem cells characterized by strong proliferative ability, multilineage differentiation (particularly advantageous for synergistic neural and vascular regeneration), and notable immunomodulatory properties, making them suitable for functional pulp-dentin regeneration [74]. Despite their critical role in REPs, ethical concerns and limitations regarding differentiation potential remain issues for stem cells [100]. Recently, cell-free therapies have emerged, utilizing exosomes derived from odontogenic stem cells. These exosomes carry bioactive components, such as miRNAs, proteins, and lipids, inherited from parent cells, effectively mimicking stem-cell paracrine effects. Animal experiments have demonstrated that exosome treatments enhance reparative dentin bridge formation and support regeneration of vascularized pulp-dentin tissues, including structures resembling dentinal tubules and odontoblast-like cells [93, 101]. This approach promotes dental pulp regeneration while addressing ethical, safety, and preservation challenges associated with traditional cell-based transplantation.

Although research involving collagen scaffolds combined with stem cells and growth factors has demonstrated regeneration of vascularized and innervated pulp-like tissues [102-103], there remains a lack of systematic approaches for reconstructing neural networks, reliable in vivo/in vitro experimental models, and methods for functional nerve assessment. Re-innervation plays a crucial role in pulp healing, whereas denervation impedes dentin formation [104-105]. These findings highlight the critical importance of neural regeneration for restoring the neurovascular function. However, limited neural regeneration success in regenerative pulp models, unlike pulp injury models, may result from the absence of a functional stem cell niche capable of secreting necessary neurotrophic factors. In rat experiments, collagen scaffolds combined rBMSCs, VEGF and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) increased the expression of neuron-specific markers (S-100, PGP9.5) and facilitated the formation of neuron-like cells and nerve terminals within regenerated tissue [102-103]. MSCs, such as DPSCs, can undergo neural differentiation, adopting Schwann cell-like phenotypes and expressing elevated levels of neural markers including paired box gene 6 (PAX6), Nestin, and β-III- tubulin, which support neurogenesis [106-107]. This strategy represents an emerging direction in peripheral nerve injury (PNI) repair [108]. However, the mechanisms underlying neurogenic processes after REPs remain poorly characterized, potentially explaining the low success rates of pulp vitality restoration. Thus, re-establishing neural structures is an essential goal in regenerative endodontics. In summary, regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex is a sophisticated spatiotemporal process.

Pulp tissue engineering using collagen-based scaffolds offers a promising approach for precise regeneration rather than mere tissue repair in REPs. Future developments in advanced collagen scaffolds that enable spatiotemporally controlled release of crucial biomolecules could better replicate the native ECM [109]. Furthermore, exploiting the paracrine capabilities of stem cells via cell- free therapies, such as exosomes or engineered extracellular vesicles containing pro-regenerative miRNAs and growth factors, may resolve challenges associated with cell sourcing, storage, and immunogenicity. However, foundational research on pulp regeneration remains limited, particularly regarding neuro-immune-vascular interactions within the pulp microenvironment. This gap in knowledge restricts the innovative design of novel collagen scaffolds for REPs. Achieving fully functional, innervated and vascularized pulp-dentin regeneration requires interdisciplinary collaboration among material scientists, biologists, and clinicians.

|

Signaling Factor |

Subtype |

Regenerative Function |

|

BMPs |

BMP2 |

Promotes odontoblastic differentiation of DPSCs [110] and facilitates dentin |

|

BMP4 |

Enhances odontoblast differentiation capacity [112]. |

|

|

BMP7 |

Promotes the transformation of DPSCs to a mineralized phenotype [113] |

|

|

BMP9 |

Promotes the differentiation and secretory function of dental pulp stem cells; it enhances cell proliferation and intercellular connections in HERS, thereby facilitating the formation of root dentin and the closure of the apical foramen [114]. |

|

|

TGF-β |

TGF-β1 |

Guides cell migration, proliferation and differentiation; stimulates |

|

TGF-β2 |

Upregulates odontogenic markers (DSPP, DMP1) and suppresses osteogenic marker bone sialoprotein in SCAPs [117] |

|

|

TGF-β3 |

Promotes odontoblastic differentiation [118] |

|

|

FGFs |

TGF-β3 |

Promotes odontoblastic differentiation [118] |

|

FGF-2 |

Regulates all stages of tooth development [119], repair, and regeneration [120], including migration, proliferation, stemness maintenance of mesenchymal stem cells, dentin formation, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis [121]. |

|

|

VEGF |

Induces endothelial differentiation of stem cells and regulates tooth development and dentin formation [122]. |

|

|

IGF |

IGF-1 |

Promotes proliferation and differentiation of DPSCs and SCAPs [123], and induces their transformation to a mineralized phenotype [124]. |

|

miRNA |

Regulates expression of key odontogenic differentiation markers; promotes neurogenesis; enhances endothelial differentiation and supports vascular regeneration [93]. |

|

|

EGF |

Enhances neurogenic differentiation of DPSCs [125] and SCAPs [126]. |

|

|

NGF |

Promotes neurite outgrowth and neural cell survival; critical for the maintenance of sympathetic and sensory neurons [127-128]. |

Table 2: Key signaling molecules in the formation of the dentin-pulp complex

Abbreviations: BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; DPSCs: dental pulp stem cells; HERS: Hertwig's epithelial root sheath; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; DSPP: dentin sialophosphoprotein; DMP1: dentin matrix protein 1; SCAPs: stem cells from the apical papilla; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor-1; miRNA: microRNA; EGF: epidermal growth factor; NGF: nerve growth factor.

CONCLUSION

Collagen scaffolds represent a highly promising biomaterial for advancing the field of regenerative endodontics. Their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to mimic the native extracellular matrix provide a conducive microenvironment for the recruitment, proliferation, and differentiation of stem cells, which is essential for the regeneration of the pulp-dentin complex. Evidence from clinical studies demonstrates that collagen scaffolds can support high survival rates and promote desirable outcomes such as pulp vitality recovery, dentin wall thickening and apical closure in necrotic immature permanent teeth, although it is not particularly adept at facilitating canal length. However, the translation of collagen-based strategies into predictable clinical protocols faces several challenges. The formation of heterogeneous mineralized tissues primarily cementum-like and bone-like tissues rather than genuine reparative dentin highlights that current REPs using collagen scaffolds often result in repair rather than true physiological regeneration. Most collagen scaffolds in current clinical or experimental use are repurposed from periodontal or implant dentistry, not designed for pulp regeneration. Hence, future work is supposed to focus on developing collagen scaffolds specifically tailored to this goal. This includes developing composite materials to enhance mechanical properties and control degradation kinetics, and meticulously optimizing key physicochemical parameters (e.g., pore size, stiffness, viscosity) to create a truly biomimetic microenvironment, integrating dental tissue engineering approaches, including seeding stem cells or incorporating bioactive molecules (e.g., miRNAs), may further guide authentic pulp tissue regeneration. Additionally, advancing cell-free strategies such as employing exosomes or engineered extracellular vesicles loaded with pro-regenerative miRNAs and growth factors could harness the paracrine potential of stem cells while overcoming challenges related to cell sourcing, storage, and immunogenicity. By addressing these challenges through interdisciplinary collaboration, collagen-based scaffolds hold immense potential to overcome the limitations of current regenerative endodontic procedures and ultimately achieve the goal of fully functional, vascularized, and innervated pulp-dentin complex regeneration.

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC2405900; No. 2022YFC2405901) and Start-up Fund of Stomatology Hospital, School of Stomatology, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (2023PDF017).

REFERENCES

- Frencken JE, Sharma P, Stenhouse L, Green D, Laverty D, et al. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis–a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017r;44:S94-105.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Miran S, Mitsiadis TA, Pagella P. Innovative dental stem cell‐based research approaches: the future of dentistry. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016(1):7231038.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Raldi DP, Mello I, MárciaHabitante S, Lage-Marques JL, Coil J. Treatment options for teeth with open apices and apical periodontitis. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75(8).[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu H, Lu J, Jiang Q, Haapasalo M, Qian J, et al. Biomaterial scaffolds for clinical procedures in endodontic regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2022;12:257-77.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Rosa V, Cavalcanti BN, Nör JE, Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Silikas N, et al. Guidance for evaluating biomaterials’ properties and biological potential for dental pulp tissue engineering and regeneration research. Dent Mater. 2025;41(3):248-64.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sui B, Chen C, Kou X, Li B, Xuan K, et al. Pulp stem cell–mediated functional pulp regeneration. J Dent Res. 2019;98(1):27-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zou J, Mao J, Shi X. Influencing factors of pulp-dentin complex regeneration and related biological strategies. Zhejiang da xuexuebao. Yi xue ban= Journal of Zhejiang University. Med Sci. 2022;51(3):350-61.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Raddall G, Mello I, Leung BM. Biomaterials and scaffold design strategies for regenerative endodontic therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2019;7:317.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Erisken C, Kalyon DM, Zhou J, Kim SG, Mao JJ. Viscoelastic properties of dental pulp tissue and ramifications on biomaterial development for pulp regeneration. J Endod. 2015;41(10):1711-7.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Quigley RM, Kearney M, Kennedy OD, Duncan HF. Tissue engineering approaches for dental pulp regeneration: the development of novel bioactive materials using pharmacological epigenetic inhibitors. Bioact Mater. 2024;40:182.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Jung IY, Lee SJ, Hargreaves KM. Biologically based treatment of immature permanent teeth with pulpal necrosis: a case series. J Endod. 2008;34(7):876-87.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Abdelsalam MS, Elgendy AA, Abu-Seida AM, Abdelaziz TM, Issa MH, et al. Histological evaluation of the regenerative potential of injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogel or collagen with blood clot as scaffolds during revascularization of immature necrotic dog’s teeth. Open Vet J 2024, 14 (11), 3004-3016.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Dave AK, Cheung JY, Kim SG. Outcomes of Regenerative Endodontic Therapy Using Dehydrated Human-Derived Amnion–Chorion Membranes and Collagen Matrices: A Retrospective Analysis. Biomimetics. 2025;10(8):530.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Jiang X, Dai Y, Liu H. Evaluation of the characteristics of root canal calcification after regenerative endodontic procedures: a retrospective cohort study over 3 years. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2023;33(3):305-313.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Theekakul C, Banomyong D, Osiri S, Sutam N, Ongchavalit L,et al. Mahidol study 2: treatment outcomes and prognostic factors of regenerative endodontic procedures in immature permanent teeth. J Endod. 2024;50(11):1569-78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zhujiang A, Kim SG. Regenerative endodontic treatment of an immature necrotic molar with arrested root development by using recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor: a case report. J Endod. 2016;42(1):72-5.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Cymerman JJ, Nosrat A. Regenerative endodontic treatment as a biologically based approach for non-surgical retreatment of immature teeth. J Endod. 2020;46(1):44-50.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Lu J, Kahler B, Jiang X, Lu Z, Lu Y. Treatment outcomes of regenerative endodontic procedures in nonvital mature permanent teeth: a retrospective study. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27(12):7531-43.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Elnawam H, Thabet A, Mobarak A, Khalil NM, Abdallah A, et al. Bovine pulp extracellular matrix hydrogel for regenerative endodontic applications: In vitro characterization and in vivo analysis in a necrotic tooth model. Head & Face Medicine. 2024;20(1):61.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Kim SG, Solomon CS. Regenerative endodontic therapy in mature teeth using human-derived composite amnion-chorion membrane as a bioactive scaffold: a pilot animal investigation. J Endod. 2021;47(7):1101-9.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Chrepa V, Joon R, Austah O, Diogenes A, Hargreaves KM, et al. Clinical outcomes of immature teeth treated with regenerative endodontic procedures-a San Antonio study. J Endod. 2020;46(8):1074-84.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Jiang X, Liu H, Peng C. Continued root development of immature permanent teeth after regenerative endodontics with or without a collagen membrane: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2022;32(2):284-93.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Tang Q, Jin H, Lin S, Ma L, Tian T, et al. Are platelet concentrate scaffolds superior to traditional blood clot scaffolds in regeneration therapy of necrotic immature permanent teeth? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2022 Dec 9;22(1):589.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Rizk HM, Al-Deen MS, Emam AA. Regenerative endodontic treatment of bilateral necrotic immature permanent maxillary central incisors with platelet-rich plasma versus blood clot: a split mouth double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2019;12(4):332.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Li J, Zheng L, Daraqel B, Liu J, Hu Y. Treatment outcome of regenerative endodontic procedures for necrotic immature and mature permanent teeth: a systematic review and Meta-analysis based on randomised controlled trials. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2023;21:b4100877.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Endodontics, A. A. o. Regenerative Endodontics. American Association of Endodontists. 2023.

- Wei X, Y. M., Yue L, et al . Expert consensus on regenerative endodontic procedures. Int J Oral Sci. 2022;14 (1):55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Jena D, Sabiha PB, Kumar NS, Ahmed SS, Bhagat P, et al. Regenerative therapy for the permanent immature teeth: a long term study. An original research. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2023;15(Suppl 1):S127-31.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Jiang X, Liu H, Peng C. Clinical and radiographic assessment of the efficacy of a collagen membrane in regenerative endodontics: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Endod. 2017;43(9):1465-71.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Haralur SB, Al-Qahtani AS, Al-Qarni MM, Al-Homrany RM, Aboalkhair AE. Influence of remaining dentin wall thickness on the fracture strength of endodontically treated tooth. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19(1):63-7.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sultan SE, Alsharaan MA, Alzhrani AA, Alruwaili MM, Kamel MM. Comparative Analysis of Regenerative Endodontic Procedures with Different Scaffold Materials. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2025;17(Suppl 2):S1246-8.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Yang F, Sheng K, Yu L, Wang J. Does the use of different scaffolds have an impact on the therapeutic efficacy of regenerative endodontic procedures? A systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):319.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Hu X, Wang Q, Ma C, Li Q, Zhao C, et al. Is etiology a key factor for regenerative endodontic treatment outcomes?. J Endod. 2023;49(8):953-62.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Abdellatif D, Iandolo A, De Benedetto G, Giordano F, Mancino D, et al. Pulp regeneration treatment using different bioactive materials in permanent teeth of pediatric subjects. J Conserv Dent Endod. 2024;27(5):458-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Mittal N, Baranwal HC, Kumar P, Gupta S. Assessment of pulp sensibility in the mature necrotic teeth using regenerative endodontic therapy with various scaffolds–Randomised clinical trial.Indian J Dent Res. 2021;32(2):216-20.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Rizk HM, Al-Deen MS, Emam AA. Pulp revascularization/revitalization of bilateral upper necrotic immature permanent central incisors with blood clot vs platelet-rich fibrin scaffolds-a split-mouth double-blind randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;13(4):337.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Yang J, Yuan G, Chen Z. Pulp regeneration: current approaches and future challenges. Front Physiol. 2016;7:58.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- ElSheshtawy AS, Nazzal H, El Shahawy OI, El Baz AA, Ismail SM, et al. The effect of platelet‐rich plasma as a scaffold in regeneration/revitalization endodontics of immature permanent teeth assessed using 2‐dimensional radiographs and cone beam computed tomography: a randomized controlled trial. Int Endod J. 2020;53(7):905-21.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Swaikat M, Faus-Matoses I, Zubizarreta-Macho A, Ashkar I, Faus-Matoses V, et al. Is revascularization the treatment of choice for traumatized necrotic immature teeth? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;12(7):2656.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Huang GT. Dental pulp and dentin tissue engineering and regeneration–advancement and challenge. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2011;3:788.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Almutairi W, Al-Dahman Y, Alnassar F, Albalawi O. Intracanal calcification following regenerative endodontic treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(4):3333-42.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Song M, Cao Y, Shin SJ, Shon WJ, Chugal N, et al. Revascularization-associated intracanal calcification: assessment of prevalence and contributing factors. J Endod. 2017;43(12):2025-33.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Markandey S, Das Adhikari H. Evaluation of blood clot, platelet-rich plasma, and platelet-rich fibrin-mediated regenerative endodontic procedures in teeth with periapical pathology: a CBCT study. Restor Dent Endod. 2022;47(4):e41.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Song M, Jung HI, Kim SG. Clinical outcomes of regenerative endodontic procedure: periapical healing, root development, and intracanalcalcification. J Endod. 2025;51(6):722-731.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Lin J, Zeng Q, Wei X, Zhao W, Cui M, et al. Regenerative endodontics versus apexification in immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Endod. 2017;43(11):1821-7.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Martin G, Ricucci D, Gibbs JL, Lin LM. Histological findings of revascularized/revitalized immature permanent molar with apical periodontitis using platelet-rich plasma. J Endod. 2013;39(1):138-44.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sugiaman VK, Jeffrey, Naliani S, Pranata N, Djuanda R, et al. Polymeric scaffolds used in dental pulp regeneration by tissue engineering approach. Polymers. 2023;15(5):1082.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Lei L, Chen Y, Zhou R, Huang X, Cai Z. Histologic and immunohistochemical findings of a human immature permanent tooth with apical periodontitis after regenerative endodontic treatment. J Endod. 2015;41(7):1172-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Austah O, Joon R, Fath WM, Chrepa V, Diogenes A, et al. Comprehensive characterization of 2 immature teeth treated with regenerative endodontic procedures. Journal of endodontics. 2018;44(12):1802-11.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Meschi N, Hilkens P, Van Gorp G, Strijbos O, Mavridou A, et al. Regenerative endodontic procedures posttrauma: immunohistologic analysis of a retrospective series of failed cases. J Endod. 2019;45(4):427-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Nosrat A, Kolahdouzan A, Khatibi AH, Verma P, Jamshidi D, et al. Clinical, radiographic, and histologic outcome of regenerative endodontic treatment in human teeth using a novel collagen-hydroxyapatite scaffold. J Endod. 2019;45(2):136-43.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Moussa DG, Aparicio C. Present and future of tissue engineering scaffolds for dentin‐pulp complex regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13(1):58-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Vyas J, Raytthatha N, Vyas P, Prajapati BG, et al. Biomaterial-Based Additive Manufactured Composite/Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers. 2025;17(8):1090.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Gao B,LvK,Shen C, Ye W, Hu W,et al. Progress of research on the formation of mineralized tissue in the root canal after dental pulp revascularization. Stomatology. 2022;42(6):571-576.

- Yamauchi N, Yamauchi S, Nagaoka H, Duggan D, Zhong S, et al. Tissue engineering strategies for immature teeth with apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2011;37(3):390-7.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zaky SH, AlQahtani Q, Chen J, Patil A, Taboas J, et al. Effect of the periapical “inflammatory plug” on dental pulp regeneration: a histologic in vivo study. J Endod. 2020;46(1):51-6.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Lui JN, Lim WY, Ricucci D. An immunofluorescence study to analyze wound healing outcomes of regenerative endodontics in an immature premolar with chronic apical abscess. J Endod. 2020;46(5):627-40.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zhu X, Wang Y, Liu Y, Huang GT, Zhang C. Immunohistochemical and histochemical analysis of newly formed tissues in root canal space transplanted with dental pulp stem cells plus platelet-rich plasma. J Endod. 2014;40(10):1573-8.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Becerra P, Ricucci D, Loghin S, Gibbs JL, Lin LM. Histologic study of a human immature permanent premolar with chronic apical abscess after revascularization/revitalization. J Endod. 2014;40(1):133-9.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Alqahtani Q, Zaky SH, Patil A, Beniash E, Ray H, et al. Decellularized swine dental pulp tissue for regenerative root canal therapy. J Dent Res. 2018;97(13):1460-7.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Altaii M, Cathro P, Broberg M, Richards L. Endodontic regeneration and tooth revitalization in immature infected sheep teeth. Int Endod J. 2017;50(5):480-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Andreasen JO, Bakland LK. Pulp regeneration after non‐infected and infected necrosis, what type of tissue do we want? A review. Dent Traumatol. 2012;28(1):13-8.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Hu N, Jiang R, Deng Y, Li W, Jiang W, et al. Periapical lesion-derived decellularized extracellular matrix as a potential solution for regenerative endodontics. Regen Biomater. 2024;11:rbae050.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Murray PE, Garcia-Godoy F. Stem cell responses in tooth regeneration. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13(3):255-62.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Mangione F, Ezeldeen M, Bardet C, Lesieur J, Bonneau M, et al. Implanted dental pulp cells fail to induce regeneration in partial pulpotomies. J Dent Res. 2017;96(12):1406-13.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Lovelace TW, Henry MA, Hargreaves KM, Diogenes A. Evaluation of the delivery of mesenchymal stem cells into the root canal space of necrotic immature teeth after clinical regenerative endodontic procedure. J Endod. 2011;37(2):133-8.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- He L, Zhong J, Gong Q, Kim SG, Zeichner SJ, et al. Treatment of necrotic teeth by apical revascularization: meta-analysis. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):13941.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Ricucci D, Siqueira Jr JF, Loghin S, Lin LM. Pulp and apical tissue response to deep caries in immature teeth: a histologic and histobacteriologic study. J Dent. 2017;56:19-32.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Shah P, Aghazadeh M, Rajasingh S, Dixon D, Jain V, et al. Stem cells in regenerative dentistry: Current understanding and future directions. Journal of Oral Biosciences. 2024;66(2):288-99.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. ProcNatlAcad Sci. 2000;97(25):13625-30.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Wu DT, Munguia-Lopez JG, Cho YW, Ma X, Song V, et al. Polymeric scaffolds for dental, oral, and craniofacial regenerative medicine. Molecules. 2021;26(22):7043.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Watt FM, Huck WT. Role of the extracellular matrix in regulating stem cell fate. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(8):467-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Murakami M, Horibe H, Iohara K, Hayashi Y, Osako Y, et al. The use of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor induced mobilization for isolation of dental pulp stem cells with high regenerative potential. Biomaterials. 2013;34(36):9036-47.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sugiaman VK, Djuanda R, Pranata N, Naliani S, Demolsky WL, et al. Tissue engineering with stem cell from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) and collagen matrix, regulated by growth factor in regenerating the dental pulp. Polymers. 2022;14(18):3712.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sumita Y, Honda MJ, Ohara T, Tsuchiya S, Sagara H, et al. Performance of collagen sponge as a 3-D scaffold for tooth-tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27(17):3238-48.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zhang W, Walboomers XF, van Kuppevelt TH, Daamen WF, Bian Z, et al. The performance of human dental pulp stem cells on different three-dimensional scaffold materials. Biomaterials. 2006;27(33):5658-68.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Ge J, Guo L, Wang S, Zhang Y, Cai T, et al. The size of mesenchymal stem cells is a significant cause of vascular obstructions and stroke. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2014;10(2):295-303.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zhang Q, Yuan C, Liu L, Wen S, Wang X. Effect of 3-dimensional collagen fibrous scaffolds with different pore sizes on pulp regeneration. J Endod. 2022;48(12):1493-501.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Bakhtiar H, Ashoori A, Rajabi S, Pezeshki‐Modaress M, Ayati A, et al. Human amniotic membrane extracellular matrix scaffold for dental pulp regeneration in vitro and in vivo. Int Endod J. 2022;55(4):374-90.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Xia Z. Biomimetic Collagen-Apatite Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering. 2014.[Google Scholar]

- Yin Z. In vitro optimization of collagen I concentration for pulp regeneration. Beijing J Stomatol. 2014.

- Bakhtiar H, Pezeshki-Modaress M, Kiaipour Z, Shafiee M, Ellini MR, et al. Pulp ECM-derived macroporous scaffolds for stimulation of dental-pulp regeneration process. Dent Mater. 2020;36(1):76-87.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Han Y, Xu J, Chopra H, Zhang Z, Dubey N, et al. Injectable tissue-specific Hydrogel System for pulp–dentin regeneration. J Dent Res. 2024;103(4):398-408.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Rosa V, Zhang Z, Grande RH, Nör JE. Dental pulp tissue engineering in full-length human root canals. J Dent Res. 2013;92(11):970-5.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Li Longbiao W, ChenglinYL. Research progress on natural scaffold in the regeneration of dental pulp tissue engineering. Int J Oral Sci. 2018;45(06):666-672.

- Sipilä KH, Drushinin K, Rappu P, Jokinen J, Salminen TA, et al. Proline hydroxylation in collagen supports integrin binding by two distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(20):7645-58.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Knight CG, Morton LF, Peachey AR, Tuckwell DS, Farndale RW, et al. The Collagen-binding A-domains of Integrins α1β1 and α2β1recognize the same specific amino acid sequence, GFOGER, in native (Triple-helical) collagens. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(1):35-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Su W, Liao C, Liu X. Angiogenic and neurogenic potential of dental‐derived stem cells for functional pulp regeneration: A narrative review. Int Endod J. 2025;58(3):391-410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Shi X, Hu X, Jiang N, Mao J. Regenerative endodontic therapy: From laboratory bench to clinical practice. J Adv Res. 2025;72:229-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Prescott RS, Alsanea R, Fayad MI, Johnson BR, Wenckus CS, et al. In vivo generation of dental pulp-like tissue by using dental pulp stem cells, a collagen scaffold, and dentin matrix protein 1 after subcutaneous transplantation in mice. J Endod. 2008;34(4):421-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Zhao Y, He J, Liang C, Hong M, Liao L, et al. G-CSF/laponite/collagen composite inducing stem cells of apical papilla homing for dental pulp regeneration. Dent Mater. 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Yu M, Liu Y, Wang Y, Wong SW, Wu J, et al. Epithelial Wnt10a is essential for tooth root furcation morphogenesis. J Dent Res. 2020;99(3):311-9.[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Mao J, Wang Y, Wang R, Jiang N, et al. Odontogenic exosomes simulating the developmental microenvironment promote complete regeneration of pulp-dentin complex in vivo. J Adv Res. 2025.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Ahmed GM, Abouauf EA, AbuBakr N, Fouad AM, Dörfer CE, et al. Cell‐Based transplantation versus cell homing approaches for pulp‐dentin complex regeneration. Stem cells international. 2021;2021(1):8483668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Min Q, Yang L, Tian H, Tang L, Xiao Z, et al. Immunomodulatory mechanism and potential application of dental pulp-derived stem cells in immune-mediated diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):8068.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Andrukhov O, Behm C, Blufstein A, Rausch-Fan X. Immunomodulatory properties of dental tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells: implication in disease and tissue regeneration. World J Stem Cells. 2019;11(9):604.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Abu Kasim NH, Govindasamy V, Gnanasegaran N, Musa S, Pradeep PJ, et al. Unique molecular signatures influencing the biological function and fate of post‐natal stem cells isolated from different sources. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;9(12):E252-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Liu Y, Liu Y, Hu J, Han J, Song L, et al. Impact of allogeneic dental pulp stem cell injection on tissue regeneration in periodontitis: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2025;10(1):239.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PloS one. 2006;1(1):e79[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sui Y, Zhou Z, Zhang S, Cai Z. The comprehensive progress of tooth regeneration from the tooth development to tissue engineering and clinical application. Cell Regen. 2025;14(1):33.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Shi J, Teo KY, Zhang S, Lai RC, Rosa V, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell exosomes enhance dental pulp cell functions and promote pulp-dentin regeneration. Biomater. Biosyst. 2023;11:100078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Wen R, Wang X, Lu Y, Du Y, Yu X. The combined application of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and bioceramic materials in the regeneration of dental pulp-like tissues. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2020;13(7):1492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Srisuwan T, Tilkorn DJ, Al-Benna S, Vashi A, Penington A, et al. Survival of rat functional dental pulp cells in vascularized tissue engineering chambers. Tissue and Cell. 2012;44(2):111-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Kvinnsland I, Heyeraas KJ, Byers MR. Regeneration of calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactive nerves in replanted rat molars and their supporting tissues. Arch Oral Biol. 1991;36(11):815-26.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Jacobsen EB, Heyeraas KJ. Effect of capsaicin treatment or inferior alveolar nerve resection on dentine formation and calcitonin gene-related peptide-and substance P-immunoreactive nerve fibres in rat molar pulp. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41(12):1121-31.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Liu Y, Zou Y, Liu X, Wang Y, Sun J, et al. The effect of differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells to glial cells on the sensory nerves of the dental pulp. Int J Dent. 2024;2024(1):3746794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Pardo-Rodríguez B, Baraibar AM, Manero-Roig I, Luzuriaga J, Salvador-Moya J, et al. Functional differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells into neuron-like cells exhibiting electrophysiological activity. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16(1):10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Sharifi M, Kamalabadi-Farahani M, Salehi M, Ebrahimi-Brough S, Alizadeh M. Recent perspectives on the synergy of mesenchymal stem cells with micro/nano strategies in peripheral nerve regeneration-a review. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024;12:1401512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Xie Z, Zhan P, Zhang X, Huang S, Shi X, et al. Providing biomimetic microenvironment for pulp regeneration via hydrogel-mediated sustained delivery of tissue-specific developmental signals. Mater Today Bio. 2024;26:101102.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Iohara K, Nakashima M, Ito M, Ishikawa M, Nakasima A, et al. Dentin regeneration by dental pulp stem cell therapy with recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2. J Dent Res. 2004;83(8):590-5.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Yang W, Harris MA, Cui Y, Mishina Y, Harris SE, et al. Bmp2 is required for odontoblast differentiation and pulp vasculogenesis. J Dent Res. 2012;91(1):58-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- About I, Laurent-Maquin D, Lendahl U, Mitsiadis TA. Nestin expression in embryonic and adult human teeth under normal and pathological conditions. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(1):287-95.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]

- Helder MN, Karg H, Bervoets TJ, Vukicevic S, Burger EH, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (osteogenic protein-1, OP-1) and tooth development. J Dent Res. 1998;77(4):545-54.[Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Crossref]