ABSTRACT

As facility agriculture advances towards high precision and energy efficiency, plant supplemental lighting strategies are shifting from static, preset methods to dynamic, perception-driven approaches. Traditional lighting recipes or empirical supplemental lighting methods often result in plant disease issues, energy waste, and photoinhibition. In recent years, hyperspectral imaging technology has emerged as a powerful, non-destructive monitoring tool, capable of capturing subtle real-time changes in plant photosynthetic pigments, water content, nitrogen levels, and early stress responses. When combined with hyperspectral imaging, machine learning enables the extraction of features and the construction of predictive models from vast spectral datasets, serving as a core driver for the early detection of plant diseases and informed decision-making. This paper systematically reviews recent advances in the integration of hyperspectral technology and machine learning for plant supplemental lighting. Furthermore, it emphasizes the critical role of machine learning models in predicting light demand, diagnosing stress, and addressing plant diseases.

Keywords: Plant Disease; Early Stress; Growth Model; Hyperspectral Technology; Machine Learning

INTRODUCTION

With the continuous growth of the global population, the increasing scarcity of arable land, and the uncertainties posed by climate change, the development of efficient and controllable facility agriculture has become an essential pathway to ensuring food security and a stable food supply [1]. In facility agriculture, light—an essential environmental factor driving photosynthesis profoundly influences plant growth through its intensity, quality, and photoperiod [2].

However, greenhouses and plant factories still predominantly rely on fixed lighting formulas or the empirical judgments of producers [3]. This reliance often leads to inefficiencies, such as "continuous supplemental lighting despite sufficient light intensity" or "unmet light requirements," resulting in significant energy waste and economic costs. Such practices can also exacerbate issues like photoinhibition [4]. The core challenge in achieving precise supplemental lighting lies in the non-destructive, rapid, and accurate quantification of plants’ real-time physiological status.

The early and precise detection of plant diseases and abiotic stresses remains a critical challenge for ensuring global food security and promoting sustainable agricultural development. In this context, the integration of hyperspectral imaging technology with machine learning methods is revolutionizing plant phenotyping and health monitoring, offering unprecedented depth of information and advanced analytical capabilities.

At the forefront of early and precise diagnostics, this technology demonstrates exceptional timeliness. Its detection capabilities surpass traditional methods, often identifying issues before visible symptoms appear. For example, in viral disease detection, achieved quantitative detection of the Tomato spotted wilt virus as early as four days post-inoculation [5]. For fungal diseases, [6]. successfully detected infections and classified anthracnose severity during the latent period, before visible symptoms emerged. Similarly, achieved an early detection rate exceeding 90% for sugarcane smut and mosaic disease [7]. In the domain of abiotic stress, hyperspectral technology has shown equally remarkable early warning capabilities: diagnosed phosphorus deficiency in cucumbers 21 days in advance; achieved precise early diagnosis of nutrient deficiencies in tomatoes, outperforming traditional computer vision methods by more than 10 days; and successfully identified plant stress caused by methane exposure, with a model accuracy of 98.2%.

More importantly, this technological paradigm is evolving from qualitative discrimination to precise quantitative analysis. In terms of growth and appearance quality, utilized hyperspectral imaging to dynamically monitor the entire growth period of tomatoes while visualizing color coordinates [8]. In the quantification of biochemical parameters, intelligently estimated chlorophyll and sugar content, while detected heavy metal lead content in rapeseed leaves and roots using deep learning and hyperspectral technology, extending its applications to environmental toxicity and food safety. Additionally, accurately classified varying severity levels of Asian rust by combining hyperspectral imaging with machine learning algorithms [9]. Similarly, validated the robustness and effectiveness of this technology across diverse application scenarios, emphasizing its potential for universal plant health monitoring [10].

Despite the promising prospects, current research still faces significant challenges, including model generalization, economic feasibility, and the complexities of multi-factor coupling. This paper aims to systematically review the progress in integrating hyperspectral technology and machine learning within the field of intelligent plant lighting, analyze the evolution of technical pathways and key bottlenecks, and forecast future development trends.

1. The Evolution of Facility Agriculture and Supplementary Lighting Technology

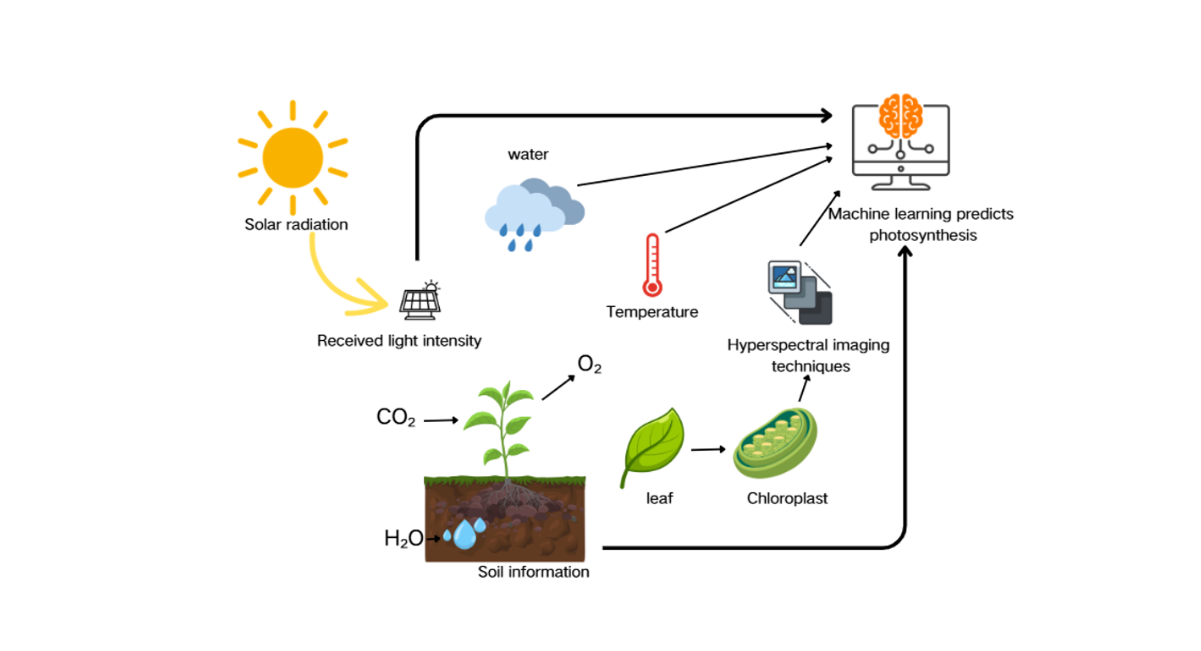

Photosynthesis is the core process by which plants convert light energy into chemical energy. By absorbing carbon dioxide and water, plants synthesize organic matter and release oxygen under light conditions [11]. This process not only underpins plant growth and energy accumulation but also plays a critical role in maintaining the carbon-oxygen balance of the Earth’s ecosystem [12]. The efficiency of photosynthesis directly influences biomass accumulation, yield formation, and the stress resistance of crops [13]. However, early water or nutrient stress can inhibit photosynthetic activity, leading to significant yield reductions [14]. Consequently, optimizing the photosynthetic process through environmental regulation has become a cornerstone of modern agriculture, particularly in the context of facility agriculture.

In the early stages of research into plant photosynthesis and light supplementation, the primary focus was on achieving plant growth through supplemental lighting [15]. introduced the concept of optimizing vertical spatial light distribution, demonstrating that while supplementary overhead lighting enhances the photosynthesis of inner leaves, additional lighting from below can further improve photosynthetic capacity under low-light conditions and significantly delay the senescence of outer leaves. Similarly [16,17]. optimized LED lamp uniformity by employing radiation measurements and enhancing light intensity distribution through the skewness formula and particle swarm algorithm, achieving more uniform illumination [18].

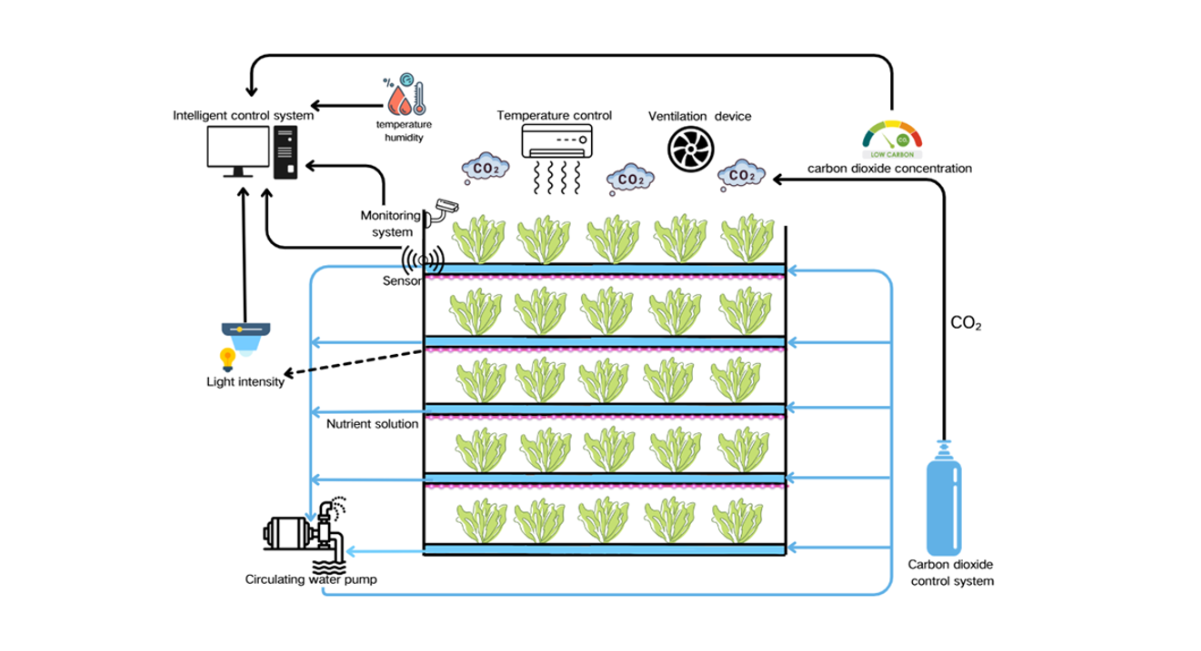

As research advanced, supplementary lighting technology evolved from focusing solely on spatial dimensions to exploring spectral dimensions. Pioneered the understanding that specific light qualities could act as non-chemical stress mitigation strategies [19]. Their study confirmed that red light and mixed blue-red spectra significantly enhance plant photosynthetic resilience by stabilizing the photosystem and increasing the electron transfer rate. Building on this, developed a hybrid lighting system that integrated movable downward lighting with adjustable lateral lighting, effectively addressing canopy shading in high-density planting systems. Meanwhile, demonstrated that extending the photoperiod significantly promotes plant growth, proposing that lighting strategies could enhance yields without disrupting ecological balance [20]. Additionally, [21]. established a plant factory, as shown in Figure 1. They adopted an integrated water and fertilizer system to cultivate crops and used machine learning to complete closed-loop control. They proposed a spectral space collaborative optimization strategy and combined the particle swarm algorithm to layout led, which improved the crop yield and energy efficiency of vertical agriculture [3].

Despite these advancements, the rapid evolution of technology has exposed inherent limitations in current research [22]. For instance, observed that while tomato seedlings in artificial light factories exhibited slower growth in early stages, grafting accelerated their growth, reduced costs, and improved survival rates [23]. Most studies, however, remain confined to single species, specific growth stages, or isolated environmental factors, lacking a comprehensive exploration of universal principles applicable across various crops. There is also a limited understanding of the complex interactions between the light environment and other factors such as temperature, humidity, and CO₂ concentration [25].

Another critical gap lies in the disconnect between technical feasibility and economic viability. While innovations such as dynamic lighting systems and agricultural photovoltaic solutions aim for energy self-sufficiency, high economic costs and energy consumption remain significant barriers to market acceptance [25]. Furthermore, the conversion of physiological indicators into economic yield outcomes remains unclear. Many studies focus on endpoints such as biomass or photosynthetic parameters, but empirical research directly linking these physiological improvements to fruit yield, quality, and economic benefits is still lacking [26].

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of an artificial plant factory integrating water and fertilizer with machine learning

1.1 The Emergence of New Technologies in Facility Agriculture

To achieve precise, efficient, and non-destructive monitoring of photosynthetic physiology, emerging spectral and intelligent analysis technologies are becoming increasingly prominent. Heckmann et al. utilized leaf reflectance spectroscopy combined with machine learning techniques to predict the photosynthetic capacity of crops [27]. Through a systematic comparison of various machine learning methods, they identified recursive feature elimination combined with partial least squares regression as the optimal modeling strategy. This approach achieved a prediction accuracy (R²) of 0.9 for the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (CN ratio), enabling high-precision prediction of photosynthetic parameters within species. The study demonstrated that this technology is an effective tool for screening superior plants in simulated breeding, offering a rapid and non-destructive solution for improving crop photosynthetic efficiency through genetic enhancement.

Addressing the challenges of energy-intensive systems in plant factories, where energy consumption is significantly higher than that of greenhouses, researchers have focused on reducing economic and environmental costs [28,29]. optimized lighting and climate control systems in artificial light plant factories using deep learning, developing an AI-powered system for a 40-foot containerized plant factory [29]. Their approach reduced energy consumption per unit yield from 9.5–10.5 kWh/kg to 6.42–7.26 kWh/kg, achieving a remarkable 32.34% energy efficiency improvement. This system outperformed traditional methods in all tested cities, demonstrating significant energy savings and supporting sustainable food production. In another study, Zou et al. examined the effects of different light intensities on tomato seedling growth in plant factories. They found that a light intensity of 240 μmol·m⁻²·s⁻¹ was optimal for tomato seedling cultivation, providing an energy-efficient alternative to greenhouse conditions [30].

While reducing energy consumption is critical, achieving high photosynthetic efficiency and productivity remains a key priority. compared the effects of three substrates and photoperiods on tomato seedlings in artificial light plant factories and developed a growth prediction model using machine learning [31]. Their findings revealed that bagged coconut coir under a 20-hour photoperiod increased seedling fresh weight by 54.9%. Furthermore, the 20-hour photoperiod boosted fresh weight by 205.2% compared to a 12-hour photoperiod. The Gradient Boosted Decision Tree (GBDT) growth prediction model achieved the highest accuracy (R² = 0.972). Economic analysis indicated that adopting a combined photoperiod strategy of 12–20 hours could save more than 20% in energy costs and enable an annual production of 21.47 batches, significantly reducing energy consumption while increasing profits.

2. Hyperspectral Non-Destructive Monitoring of Plant Virus Damage

Whether for energy conservation or efficiency improvement, the optimization of supplementary lighting strategies depends on a precise understanding of the internal physiological state of plants [32]. Hyperspectral technology has emerged as a crucial bridge between plant physiological state monitoring and external decision-making in supplementary lighting strategies [8]. Its core advantage lies in its ability to simultaneously capture spectral information across hundreds to thousands of continuous bands per pixel without contact or damage to plants [33]. This capability to reveal the internal physiological status of plants, combined with rapid data acquisition, makes hyperspectral technology an advanced tool for optimizing plant lighting strategies and advancing precision agriculture [34].

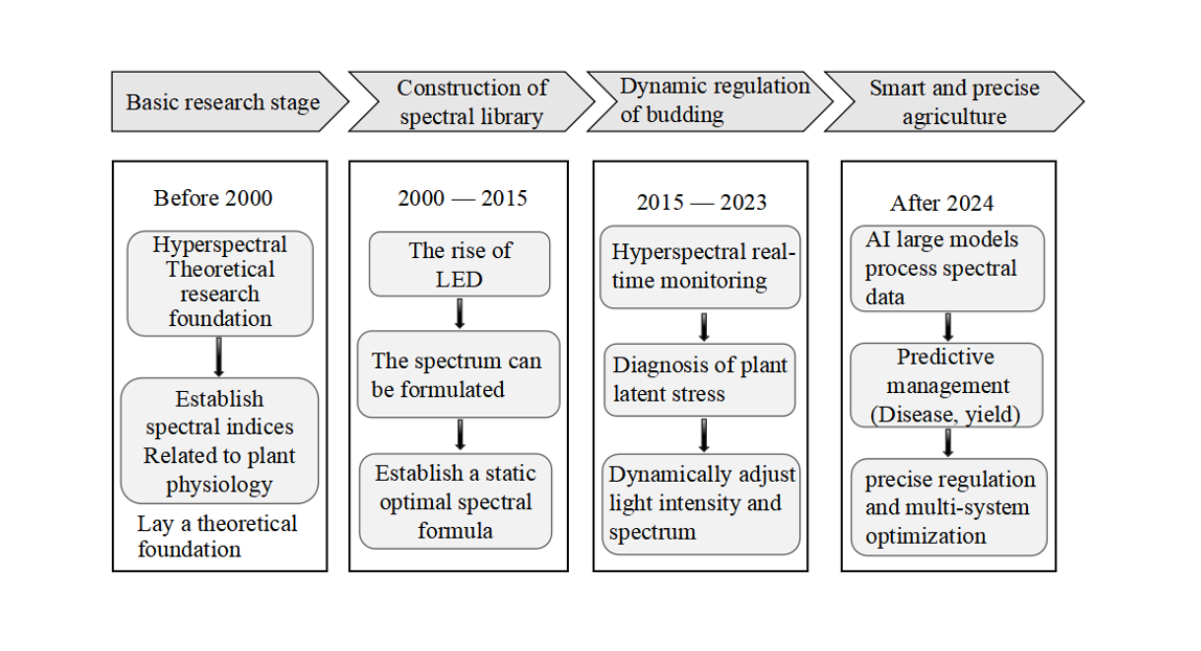

The core value of hyperspectral technology lies in its integration of morphological imaging with detailed spectral analysis [35]. As shown in Figure 2, the application of hyperspectral technology in plant monitoring has been continuously developing with the advancement of technology. Early research primarily focused on developing linear inversion models to estimate pigments such as chlorophyll using visible-near infrared spectroscopy [36]. For example, employed the CARS-PLSR algorithm to visualize SPAD values in pumpkin leaves, achieving a prediction accuracy (R²) of 0.9187 [36]. With technological advancements, hyperspectral applications have expanded to include early diagnoses of water stress. developed a compact hyperspectral system that achieved classification accuracy exceeding 90% four days before drought-induced stress in lettuce, demonstrating exceptional early warning capabilities [37,38].

Recent research has further advanced the understanding of photosynthetic functions. In 2023, Han et al. demonstrated that spectral data processed using first-order differentiation combined with the LightGBM algorithm could accurately predict leaf photosynthetic rate (Pn) with R² > 0.97. The photochemical reflectance index (PRI, e.g., 531 nm) was found to significantly correlate with the xanthophyll cycle induced by supplementary lighting (r = 0.89–0.94), making it an effective indicator for quantifying light energy use efficiency [39]. In 2024, hyperspectral imaging technology combined with chemometric methods to achieve non-destructive detection of sunflower seed viability and moisture content [36].

Figure 2: A development trajectory diagram of hyperspectral non-destructive monitoring of plant health

2.1 Hyperspectral Monitoring of Plant Health to Detect Diseases

Hyperspectral technology has proven to be an effective tool for monitoring viral diseases in plant factories. For example, Justus et al. analyzed the progression of beet leaf spot using time-series hyperspectral imaging. When compared to non-imaging spectrometers, the correlation coefficient of the calibration board measurements exceeded 0.99. By training a convolutional neural network on the collected data for disease pixel classification, they achieved 62% accuracy in estimating the severity of brown spot, effectively tracking disease progression over time.

Beyond disease monitoring, hyperspectral technology can also be utilized to detect plant drought stress, enabling timely human intervention to ensure normal plant growth. Qin et al. developed a compact hyperspectral plant health monitoring system that controlled 12 lettuce plants under normal watering and a drought treatment with 100 ml less water [38]. Hyperspectral images were continuously collected over 13 days, starting from the first day of stress. Their system achieved classification rates exceeding 90% within the first four days of stress, demonstrating its capability to provide early warnings of drought stress before visible symptoms appear.

In addition, hyperspectral technology has the ability to quantify plant photosynthesis. Chlorophyll concentration, a direct indicator of photosynthetic capacity, can be effectively measured using hyperspectral imaging. By analyzing the spectral reflectance characteristics of leaves in the visible-to-near-infrared range (380–1030 nm), chlorophyll prediction models can be established [40]. confirmed experimentally that a higher proportion of red light led to increased chlorophyll content and photosynthetic rates in cucumber seedlings [3]. Zhao Yanru et al. proposed a methodology for creating a visual distribution map of the relative chlorophyll content (SPAD value) in pumpkin leaves. This was achieved through hyperspectral imaging combined with the Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS) algorithm and Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), yielding a prediction accuracy of R² = 0.918.

The advantages of hyperspectral imaging in plant health detection are increasingly evident. Hyperspectral imaging captures the spectral characteristics of plants within the 350–750 nm visible light range, particularly in two highly correlated regions: 350–450 nm and 600–750 nm. This enables non-destructive monitoring of dynamic changes in leaf photosynthetic rate (Pn) and the fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (FAPAR) under supplementary lighting conditions [39]. Furthermore, hyperspectral imaging can detect subtle variations in physiological parameters such as chlorophyll content, water stress, and early disease symptoms. Its resolution significantly surpasses that of traditional multispectral technology [41].

Research has demonstrated the potential of hyperspectral data combined with machine learning algorithms for accurate physiological predictions. For instance, first-order derivative processed spectral data combined with the LightGBM algorithm (learning rate = 0.053 and 479 iterations) achieved accurate inversion of leaf Pn (R² > 0.97). In contrast, the Random Forest model (87 decision trees and 68 node variables) exhibited superior predictive performance for canopy FAPAR (RPD > 1.4). This discrepancy reflects the higher representation capability of spectral information at the canopy scale for quantifying light use efficiency [42].

Compared to traditional point measurement devices, such as SPAD meters, hyperspectral imaging offers significant advantages. By reducing information redundancy in full-band analysis through feature band selection, hyperspectral imaging lowers the cost per measurement by over 80%, while enabling continuous monitoring at the acre-level field scale [43]. This makes it an invaluable tool for precision agriculture and large-scale plant health monitoring.

In conclusion, current research consistently indicates that the application value of hyperspectral imaging in plant factories and precision agriculture is constantly emerging. Whether it is viral diseases, early drought stress, or the quantitative estimation of photosynthetic parameters and chlorophyll content, hyperspectral technology has demonstrated accuracy and timeliness far exceeding traditional detection methods. Its advantages and application scope are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Application cases of hyperspectrum in Plant Diseases and health

|

Researcher |

Application Direction |

Study Object |

Core Methods |

Key Performance / Metrics |

Research Value & Advantages |

|

& Models |

|||||

|

Justus et al. |

Viral Disease Monitoring |

Beet Leaf Spot |

Time-series hyperspectral imaging; CNN for disease pixel classification |

Correlation with calibration panel > 0.99; Brown spot severity estimation accuracy: 62% |

Enables effective tracking and quantitative assessment of disease progression. |

|

Qin et al. |

Drought Stress Early Warning |

Lettuce Drought Stress |

Compact hyperspectral system; Continuous imaging for 13 days |

Classification rate > 90% within the first 4 days of stress |

Provides early warning before visible symptoms appear, facilitating timely human intervention. |

|

Zhao Yanru et al. |

Photosynthesis Quantification |

Cucumber/Pumpkin Leaf Chlorophyll |

VIS-NIR spectral analysis (380-1030 nm); CARS-PLSR modeling |

Chlorophyll SPAD prediction accuracy: RC = 0.918 |

Quantifies the relationship between chlorophyll content and light quality (e.g., red light ratio); enables visual distribution mapping. |

|

Han et al. |

Photosynthetic Physiology Monitoring |

Leaf Pn & Canopy FAPAR |

Spectral feature analysis (350-750 nm); LightGBM & Random Forest algorithms |

Leaf Pn inversion R² > 0.97; Canopy FAPAR prediction RPD > 1.4 |

Enables non-destructive, dynamic monitoring of Pn and FAPAR; accuracy significantly surpasses traditional point-measurement devices. |

|

Huang et al. |

General Technical Advantages |

Various Physiological Parameters |

Full-band data analysis & feature band selection |

Cost per measurement reduced by > 80% |

Overcomes information redundancy; supports continuous, large-scale (acre-level) field monitoring; resolution far exceeds multispectral technology. |

3. Machine Learning in Intelligent Decision-Making

Machine Learning (ML), a core branch of Artificial Intelligence, aims to enable computer systems to autonomously learn patterns or regularities from data through algorithms, allowing them to make predictions or decisions without relying on explicit programming. The core concept of ML lies in feature extraction, model construction, and continuous performance optimization. It has found widespread applications in fields such as image classification, spectral analysis, and agricultural monitoring [44].

3.1 The Algorithmic Evolution from Traditional Models to Deep Networks

The key to processing plant physiological data lies in dimensionality reduction and feature extraction. In 2016, SHOGO et al. demonstrated the use of machine learning to predict plant growth with high accuracy based on chlorophyll fluorescence and plant physiological indicators [45]. Subsequently, algorithms such as Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) have been widely applied in plant science. For instance, in 2017, [27]. utilized Recursive Feature Elimination combined with PLSR (RFE-PLSR) to predict photosynthetic capacity [27].

In 2020, used key plant growth indicators such as plant height, leaf density, respiration rate, photosynthetic rate, and crop yield to study the effects of environmental factors, including lighting, temperature, humidity, CO₂ concentration, and nutrient solution concentration, in plant factories. By employing deep learning techniques, they established and optimized plant growth models to promote growth and increase yield. Similarly, developed estimation models for greenhouse lettuce growth parameters using both deep learning and traditional machine learning techniques, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forests (RF), and Logistic Regression (LR). The study revealed that the deep learning-based CNN model outperformed shallow machine learning models, achieving group estimation accuracies exceeding 90%.

In 2022, created a comprehensive image database documenting the entire growth process of rapeseed [46]. They applied a deep learning method (EPSA-YOLO-V5s) to identify non-viable rapeseed plants during the early and middle growth stages, addressing issues of energy and space waste caused by cultivating seedless rapeseed during production. This breakthrough highlighted the potential of deep learning to optimize agricultural resource usage.

In 2025, explored approaches to accelerate photosynthesis using machine learning [47]. By integrating genetic algorithms, they successfully reverse-engineered and developed a "cooling canopy film" to enhance photosynthesis. This innovative film employs spectral screening to selectively transmit the 400–500 nm (blue light) and 600–700 nm (red light) bands essential for photosynthesis, while efficiently reflecting the majority of the remaining solar spectrum—particularly the near-infrared heat portion. This advancement significantly improved light use efficiency while reducing heat stress, offering a promising solution for sustainable agriculture.

In conclusion, in recent years, data-driven methods centered on machine learning and deep learning have become the key technical paths for processing plant physiological information and optimizing intelligent production. Traditional methods such as PLSR and SVM still play significant roles in feature extraction, variable selection, and modeling of small and medium-sized samples. Meanwhile, strategies like recursive feature elimination further enhance the model's predictive ability for key physiological indicators such as photosynthetic parameters. Meanwhile, deep learning models, with their powerful expression capabilities for high-dimensional, nonlinear physiological and image data, have significantly outperformed shallow models in tasks such as crop growth estimation, phenotypic recognition, and early differentiation of good and bad seedlings, gradually becoming the mainstream approach in plant factory and facility agriculture research. Overall, these studies have demonstrated the great potential and diverse application scenarios of data-driven methods in plant production. Their main features and technological advancements are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Research Progress of Machine Learning in Plant Growth

|

Year |

Researcher |

Research object |

Key algorithm |

Application objective |

Research Findings |

|

2016 |

SHOGO et al. |

Chlorophyll fluorescence and plant indicators |

Neural network |

Predict plant growth |

Developed an automatic system |

|

2017 |

Heckmann et al. |

Leaf reflection spectrum |

RFE-PLSR |

Predict photosynthetic capacity |

The REE-PLSR model performed best (R² = 0.9). |

|

2020 |

ZHENG et al. |

Environmental factors and plant growth status |

Deep learning |

Promote growth and increase yield |

Convolutional Neural Networks can increase population estimation accuracy to over 90%. |

|

2020 |

XU Dan et al. |

Greenhouse lettuce images or data |

CNN、SVR、RF、LR |

Predict plant growth |

Reduced waste in rapeseed production. |

|

2022 |

ZHANG et al. |

Images of the entire growth process of rapeseed |

EPSA-YOLO-V5s |

Accurately identify unsurvived plants |

Designed and fabricated films to enhance the photosynthetic rate. |

|

2025 |

Li et al. |

Spectral requirements of photosynthesis |

Neural network |

Promote photosynthesis |

Increased accuracy to over 90%, reducing waste in rapeseed production. |

3.2 The Implementation of a Closed-Loop Control System

At the perceptual level, machine learning has significantly improved the speed and depth of collecting plant spectral information. For instance, Zeng et al. demonstrated that by training a lightweight convolutional neural network, spectral information could be rapidly reconstructed from compressed, mixed-encoded LED measurement data, increasing imaging and reconstruction speeds by over 180 times [48]. Furthermore, by employing models such as discriminant analysis, accurate early warnings with over 90% accuracy were achieved four days before the onset of drought stress based on vegetation spectral features. These insights enabled LED systems to automatically switch to blue-green light to promote growth during the vegetative stage and to red light to enhance maturity during the flowering and fruiting stages. This intelligent closed-loop system of "perception–decision–regulation" significantly enhances the efficiency of light energy utilization and plant productivity [50].

In addition to indirect perception based on spectral data, integrating direct plant physiological signals can make decision-making models more precise and better aligned with energy-saving goals. For instance, Afagh et al. monitored stem sap flow dynamics using electrochemical impedance sensors and conducted comparative studies leveraging machine learning methods to derive sensor coefficients for measuring photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) [50]. Their findings showed that decision tree and random forest models achieved mean absolute percentage errors of 0.01%–0.88% on the red and blue channels, respectively. Additionally, linear regression models were used to identify periods of optimal light efficiency. This approach enabled light-adaptive regulation, resulting in energy savings of 25%–30% and shortening the plant growth cycle.

Zou et al. further contributed to this field by demonstrating how an optimized red-to-blue light ratio of R8B2 could accelerate the growth of butter lettuce and improve its quality. By optimizing the lighting layout through advanced algorithms, they were able to enhance the uniformity of light distribution, thereby maximizing the efficiency of the supplemental lighting system.

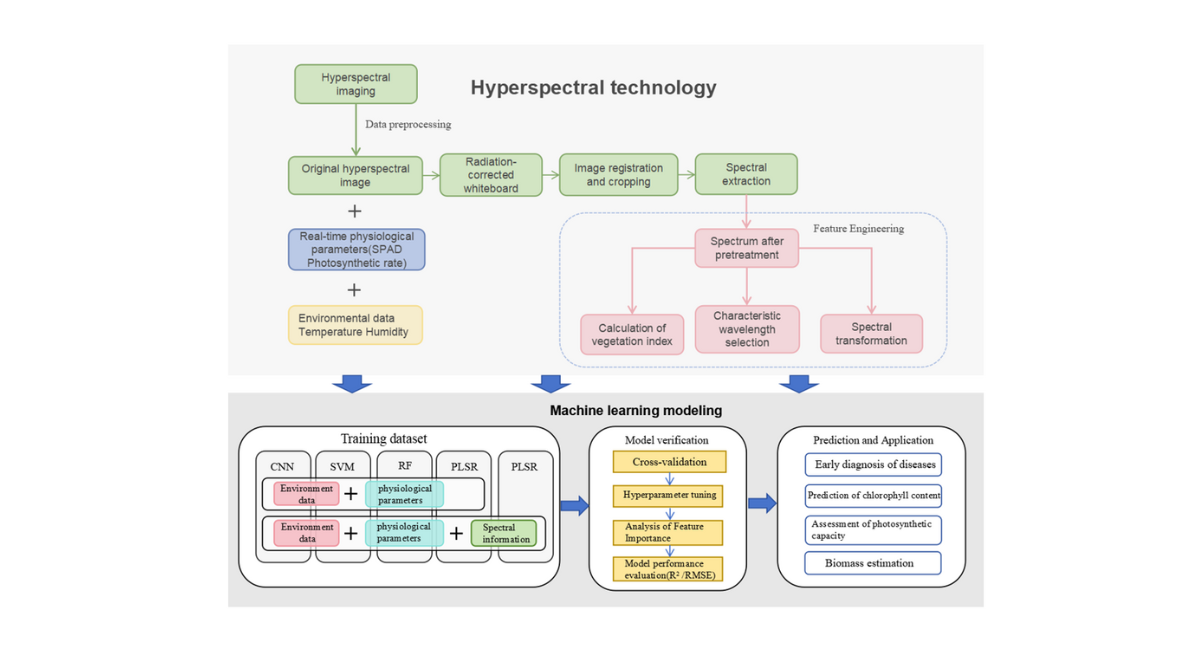

Figure 3: Closed-loop diagram of the intelligent supplementary lighting system

To achieve the aforementioned adaptive control, precise plant image recognition is a crucial preliminary step, and this is a domain where machine learning excels. As shown in Figure 3, after Hyperspectral collects a large amount of data, it uses machine learning to build a model, train the dataset, and make predictions based on it, thereby achieving closed-loop control. Sajad et al. developed a machine vision-based plant image segmentation system designed for automatic plant recognition under varying lighting conditions [51]. They employed a hybrid artificial neural network combined with a harmony search algorithm to optimize the classification of multiple color space features, achieving a segmentation accuracy of up to 99.69% with an average processing time of only 0.37 seconds per image. This fast and accurate image recognition capability provides critical technical support for the subsequent implementation of adaptive lighting control.

In terms of optimizing supplementary lighting strategies, the effect of supplemental lighting is quantified by altering the spectral response characteristics involved in the plant photomorphogenesis process. demonstrated that under uniform light, a red-to-blue light ratio of R8B2 enabled Spanish lettuce to achieve optimal growth and yield [17]. Furthermore, the photochemical reflectance index (PRI) at specific wavelengths (e.g., 531 nm) was found to be significantly correlated with the xanthophyll cycle induced by supplementary lighting (r = 0.89–0.94). Additionally, changes in reflectance within the 600–690 nm range directly reflected the regulatory effects of supplemental lighting on the chlorophyll a/b ratio [52].

Machine learning models have successfully deciphered the coupling mechanism between supplemental light intensity and nitrogen use efficiency by integrating nonlinear relationships across multispectral dimensions. Specifically, when the spectral peak of supplemental light was located in the 450 nm blue light region, each 100 μmol·m⁻²·s⁻¹ increase in light intensity improved nitrogen assimilation efficiency by 12.7%. This conclusion was validated through Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) analysis of principal component variables derived from continuum-removed derivative reflectance (PCA_CRDR_R) [53]. These findings provide a physiological basis for optimizing supplemental lighting strategies. For instance, employing a red-to-blue light ratio of 6:4 during the reproductive growth stage of cotton increased the photosynthetic carbon assimilation rate by 23% while reducing nitrogen fertilizer application by 15% [54].

Moreover, the ratio of red-to-blue light has varying effects on plant growth. Zou et al. found that higher red-to-blue light ratios promote vertical growth, whereas lower ratios are more beneficial for root development and tillering.These variations underline the importance of tailoring light strategies to specific growth stages and crop requirements.

In summary, these applications clearly delineate a technological pathway, illustrated in Figure 3, where machine learning—by enabling rapid spectral reconstruction, multi-source signal fusion, and precise image recognition—constructs models that serve as the core technology driving the realization of intelligent lighting systems. However, the actual effectiveness and economic benefits of these optimization strategies still require systematic evaluation for validation.

4. Technical and Economic Analysis and Application Challenges

Machine learning provides innovative solutions for balancing the benefits and costs of supplemental lighting through data-driven modeling and dynamic decision-making. For instance, by analyzing the correlation between leaf spectral characteristics and photosynthetic efficiency using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), differentiated supplemental lighting strategies have been developed, reducing energy consumption by 20%–25% compared to traditional fixed lighting schemes [33]. In cucumber greenhouse experiments, the Random Forest (RF) model, which integrates light intensity, spectral composition, and plant phenotypic data, improved supplemental lighting efficiency by 15% while reducing electricity costs associated with ineffective lighting.

Reinforcement learning frameworks further optimize yield targets while adhering to energy consumption constraints through reward function design. A case study in Dutch tomato greenhouses demonstrated that this method reduced energy consumption per unit yield by 18% [40]. Similarly, in Gerbera cultivation, the XGBoost model, constructed using drone-collected multispectral data, recommended dynamically adjusting the red-to-blue light ratio, shortening the growth period by 7 days while maintaining the flowering rate and increasing the total seasonal profit by 12%. This approach also reduced hardware costs, making intelligent lighting systems more accessible to small farms [56].

Economic evaluation models reveal that hyperspectral-machine learning systems deployed on drone platforms have cost advantages for large-scale applications exceeding 500 mu. Compared to traditional methods involving manual sampling and laboratory analysis, this technology reduces the cost of single nutrient diagnosis from ¥12.8/plant to ¥0.3/plant, shortening the investment return period to just 2.3 years [50]. developed a windmill vertical tillage system for efficient strawberry cultivation under low-light conditions, which was optimized using the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm. The algorithm-driven lighting layout significantly improved the asexual reproduction and reproductive performance of vertically cultivated strawberries while maintaining high energy efficiency [57].

One particularly noteworthy advancement is in the deployment of prediction models. By employing transfer learning strategies, prediction models such as the XGBoost regularization model maintained 83.2% accuracy under varying supplementary lighting conditions in field environments. This generalization capability significantly reduces the marginal cost of technology promotion. Practical applications, such as variable-rate LED lighting in apple orchard management, demonstrated that this technology increased the soluble solid content of fruits by 19% while reducing energy consumption costs by 31%, thereby validating its dual value in "precision control and energy efficiency optimization" [44].

Zou et al. also designed an automatic lighting detection device to study the influence of different red and blue light intensities on two lettuce varieties in vertical farms. Their results showed that butter lettuce achieved optimal yields under a light intensity of 300 μmol/m²/s, while Spanish green lettuce achieved similar productivity under a lower light intensity of 200 μmol/m²/s, making it more energy-efficient. The ongoing challenge lies in identifying the balance point to achieve high crop yields at minimal cost [57].

5. Discussion and Outlook

This article systematically reviews the research progress of hyperspectral technology and machine learning in the field of plant supplemental lighting. The review highlights that through non-destructive detection and data collection enabled by hyperspectral technology, machine learning facilitates intelligent decision-making, enabling dynamic and precise supplemental lighting. These advancements address the core issues of high energy consumption and low efficiency in current facility agriculture. Hyperspectral technology offers both depth and breadth for understanding the photophysiological state of plants, while machine learning empowers the extraction of effective features from massive spectral data, the construction of predictive models, and the provision of decision-making capabilities.

However, despite the significant potential demonstrated by laboratory research and pilot projects, transitioning this technology from concept to large-scale commercialization still faces numerous challenges.

5.1 Bottlenecks and Critical Thinking in Current Technological Convergence

While hyperspectral imaging generates extremely rich data, this also constitutes one of its primary bottlenecks [58]. The high cost of hyperspectral equipment, the complexity of data processing, and the computational resources required to handle massive datasets remain in stark contrast to the real-time, low-cost, and high-throughput demands of agricultural applications [59]. Although research on lightweight CNN models and similar approaches has made strides in accelerating data processing, for closed-loop supplemental lighting systems requiring minute-level or even second-level responses, the latency and cost of current technologies remain significant obstacles.

Figure 4: Flowchart of the integration of hyperspectral and machine learning technologies

Future research needs to prioritize the development of low-cost, high-robustness dedicated spectral sensors and ultra-efficient algorithms capable of running on edge computing devices. While many current models, such as those based on random forests or deep learning, achieve high accuracy (R² > 0.9) on specific datasets, they are often regarded as "black boxes." This lack of interpretability limits their acceptance by plant physiologists and agronomists, as it is difficult to understand or trust the model’s recommendations—such as why increasing the proportion of blue light might be preferable to red light at a particular moment.

A more critical issue lies in model generalization. Models trained on specific crop varieties, growth stages, and environmental conditions often fail to perform well when applied to other varieties or greenhouse environments. This lack of universality significantly limits their practical applications. Moving forward, integrating explainable AI with plant photophysiological mechanisms, along with cross-species and cross-environment transfer learning strategies, will be essential to overcoming these challenges.

Additionally, much of the current research focuses on "light" as a single factor, even though plant growth is influenced by a complex interplay of multiple factors, including light, temperature, water, nutrients, and CO₂ [60]. Intelligent systems capable of synergistically regulating supplementary lighting, heating, irrigation, and fertilization are still in their infancy [61]. Neglecting the coupling effects between these factors can lead to suboptimal or even ineffective supplementary lighting strategies in real-world production. As shown in Figure 4, developing a multimodal fusion learning framework based on "plant digital twins" is a critical step toward achieving truly intelligent management and control [61].

6. Future Development Direction

Based on the above discussion, future supplemental lighting systems will no longer rely on fixed red-to-blue ratios or photoperiods. Instead, they will utilize a "dynamic light spectrum" that adjusts light intensity, spectrum, and photoperiod dynamically according to the plant’s real-time physiological needs, growth stages, and production goals. This shift will enable "on-demand lighting" to optimize plant growth and resource efficiency [62].

To meet real-time requirements, future trends point toward deploying trained lightweight models on edge computing devices. This strategy will allow data collection, analysis, and decision-making to occur directly within greenhouses or plant factories, eliminating the dependence on cloud computing and enabling real-time closed-loop control of the lighting [63,64].

From an economic perspective, future efforts should focus on reducing the initial investment threshold for small farms. Modular system designs, open-source algorithms, and low-power hardware can make these technologies more accessible and affordable [65,66]. Additionally, conducting detailed lifecycle economic benefit analyses will attract industrial capital investment and accelerate the commercialization of these technologies [67].

In summary, the integration of hyperspectral technology and machine learning is transforming plant lighting technology in unprecedented ways [68]. However, to fully realize its potential, breakthroughs are needed to address core challenges such as the data paradox, the "black box" nature of models, and the complexities of multi-factor coupling. By advancing inclusivity, scalability, and integration, this technology can achieve its ultimate goal: enabling high yield, high quality, low carbon, and sustainable development in facility agriculture [69].

In summary, the convergence of supplemental lighting, hyperspectral sensing, and machine learning has the potential to transform controlled-environment agriculture from experience-driven management to intelligent, plant-centered decision-making. Realizing this potential will require a shift toward integrated, interpretable, and economically viable solutions that align technological innovation with practical production needs [70-80].

CONCLUSION

This review critically synthesizes recent advances in supplemental lighting optimization, hyperspectral sensing, and machine-learning–based decision support for controlled-environment agriculture. Rather than treating these components as isolated technologies, the manuscript frames their convergence as a paradigm shift from experience-driven lighting management toward intelligent, plant-centered, and data-driven control systems.

The analysis reveals that while spectrum-specific and dynamic lighting strategies have demonstrated clear benefits for crop growth, quality, and energy efficiency, most existing approaches remain fundamentally static and empirically derived. Hyperspectral sensing provides a powerful means to capture real-time plant physiological status, yet its full potential is often constrained by data dimensionality, computational demands, and limited integration with lighting control. Machine learning enables effective extraction of actionable information from complex spectral data, but trade-offs between predictive accuracy, interpretability, and generalization continue to limit large-scale deployment.

By systematically examining these challenges, this review identifies four central bottlenecks: the reliance on predefined lighting strategies rather than plant-driven control, the conflict between sensing accuracy and real-time applicability, the tension between model performance and interpretability, and the limited transferability of models across crops and environments. Addressing these issues requires a shift from component-level optimization toward system-level integration, where sensing, modeling, and control operate within a closed-loop framework.

Looking forward, future research should prioritize dynamic and demand-driven lighting strategies, cost-effective sensing solutions, interpretable and transferable modeling approaches, and comprehensive economic and sustainability assessments. Progress along these directions will be essential for translating laboratory-scale innovations into robust, scalable, and commercially viable lighting management systems.

Overall, this review provides a structured and critical perspective on the evolving landscape of intelligent lighting control in controlled-environment agriculture, offering both a synthesis of current knowledge and a roadmap for future research and practical implementation.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript is a review article and does not report original research data. All figures and tables presented herein are original creations of the authors and are included within this article.

DECLARATIONS

Ethical approval the author confirms that there are no ethical issues in publication of the article.

Competing interests the author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Shanghai Science and Technology Committee Science and Technology Innovation Program (Grant No. 25N32800300,Grant No. 23N21900100). Shanghai Key Laboratory of Protected Horticulture Technology (Grant No. KF202506)

REFERENCES

- Kluczkovski A, Hadley P, Yap C, Ehgartner U, Doherty B, et al. Urban vertical farming: innovation for food security and social impact?. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2025;380(1935). [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi J, Wang Y, Li Z, Huang X, Shen T, et al. Characterization of invisible symptoms caused by early phosphorus deficiency in cucumber plants using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging technology. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2022;267:120540. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin D, Su X, Li Y, Shi M, Yang B, et al. Effect of red and blue light on cucumber seedlings grown in a plant factory. Horticulturae. 2023;9(2):124. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MH, Islam MJ, Mumu UH, Ryu BR, Lim JD, et al. Effect of Light Quality on Seed Potato (Solanum tuberose L.) Tuberization When Aeroponically Grown in a Controlled Greenhouse. Plants. 2024;13(5):737. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee G, Hossain O, Jamalzadegan S, Liu Y, Wang H, et al. Abaxial leaf surface-mounted multimodal wearable sensor for continuous plant physiology monitoring. Science Advances. 2023;9(15):eade2232. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siripatrawan U, Makino Y. Hyperspectral imaging coupled with machine learning for classification of anthracnose infection on mango fruit. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2024;309:123825. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bao D, Zhou J, Bhuiyan SA, Adhikari P, Tuxworth G, et al. Early detection of sugarcane smut and mosaic diseases via hyperspectral imaging and spectral-spatial attention deep neural networks. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2024;18:101369. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Ji S, Shi Y, Xuan G, Jia H, et al. Growth period determination and color coordinates visual analysis of tomato using hyperspectral imaging technology. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2024;319:124538. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santana DC, de Queiroz Otone JD, Baio FH, Teodoro LP, Alves ME, et al. Machine learning in the classification of asian rust severity in soybean using hyperspectral sensor. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2024;313:124113. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stegemann J, Gröniger F, Neutsch K, Li H, Flavel BS, et al. High‐Speed Hyperspectral Imaging for Near Infrared Fluorescence and Environmental Monitoring. Advanced Science. 2025;12(16):2415238. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai J, Kooijmans LM, Sun W, Lombardozzi D, Campbell JE, et al. Terrestrial photosynthesis inferred from plant carbonyl sulfide uptake. Nature. 2024;634(8035):855-61. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paul C, Piel C, Sauze J, Yang JW, Bouchet M, et al. Air oxygen fractionation associated with respiration and photosynthesis processes in plants: impact on the study of the global Dole effect. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2025;370:109663. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza AP, Burgess SJ, Doran L, Hansen J, Manukyan L, et al. Soybean photosynthesis and crop yield are improved by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science. 2022;377(6608):851-4. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rath M, Bergmann D. Evolutionary innovation hints at ways to engineer efficient photosynthesis in crops. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Croce R, Carmo-Silva E, Cho YB, Ermakova M, Harbinson J, et al. Perspectives on improving photosynthesis to increase crop yield. The plant cell. 2024;36(10):3944-73. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joshi J, Zhang G, Shen S, Supaibulwatana K, Watanabe CK, et al. A combination of downward lighting and supplemental upward lighting improves plant growth in a closed plant factory with artificial lighting. HortScience. 2017;52(6):831-5. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luo S, Zou J, Shi M, Lin S, Wang D, et al. Effects of red-blue light spectrum on growth, yield, and photo-synthetic efficiency of lettuce in a uniformly illumination environment. Plant, Soil & Environment. 2024;70(5). [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wang X, Zhang X, Wang D, Xu X. A band selection method combining spectral color characteristics for estimating chlorophyll content of rice in different backgrounds. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2025;330:125681. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malekzadeh MR, Roosta HR, Esmaeilizadeh M, Dabrowski P, Kalaji HM. Improving strawberry plant resilience to salinity and alkalinity through the use of diverse spectra of supplemental lighting. BMC Plant Biology. 2024;24(1):252. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fraser JL, Abram PK, Dorais M. Supplemental LED lighting improves plant growth without affecting biological control in a tri-trophic greenhouse system. bioRxiv. 2023:2023-04. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Liu W, Wang D, Luo S, Shen Y, et al. (2024). The impact of varying ratios of light quality emitted by light-emitting diodes (LEDs) on the butter lettuce. Journal of Optics and Photonics Research. [Crossref]

- Zou J, Liu W, Wang D, Luo S, Yang Set al. Comparative study of artificial light plant factories and greenhouse seedlings of SAOPOLO tomato. Plos one. 2025;20(3):e0314808. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu C, Li R, Wu S, Miao C, Zhang Y, et al. Construction of a tomato seedling growth model and economic benefit analysis under different photoperiod strategies in plant factories. Horticultural Plant Journal. 2025. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk AD, Kootstra G, Kruijer W, de Ridder D. Machine learning in plant science and plant breeding. Iscience. 2021;24(1). [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raychaudhuri S, Challa T. Challenges in the design & development of efficient (High Power) lighting systems. 2025:172495. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan YD, Hartanto W, Lukas EE, Julienne ND, et al. Smart plant watering and lighting system to enhance plant growth using internet of things. Procedia Computer Science. 2023;227:966-72. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heckmann D, Schlüter U, Weber AP. Machine learning techniques for predicting crop photosynthetic capacity from leaf reflectance spectra. Molecular plant. 2017;10(6):878-90. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen X, Ji Y, Wu G, Zang J, Lu L, et al. Optical and thermal performance of a spectral-splitting transmission/photovoltaic system for plant factories. Energy. 2025;336:138304. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Decardi-Nelson B, You F. Artificial intelligence can regulate light and climate systems to reduce energy use in plant factories and support sustainable food production. Nature Food. 2024;5(10):869-81. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng Y, Zou J, Lin S, Jin C, Shi M, et al. Effects of different light intensity on the growth of tomato seedlings in a plant factory. Plos one. 2023;18(11):e0294876. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Tang Y, Zhu XG. Stomata conductance as a goalkeeper for increased photosynthetic efficiency. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2022;70:102310. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu S, Nakagawa W, Mori Y, Azhari S, Méhes G, et al. A plant-insertable multi-enzyme biosensor for the real-time monitoring of stomatal sucrose uptake. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2025:117674. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu B, Dao PD, Liu J,

- Y, Shang J. Recent advances of hyperspectral imaging technology and applications in agriculture. Remote Sensing. 2020;12(16):2659. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A, Chandel NS, Singh KP, Chakraborty SK, Nandede BM, et al. Deep learning and computer vision in plant disease detection: a comprehensive review of techniques, models, and trends in precision agriculture. Artificial Intelligence Review. 2025;58(3):92. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Sanaeifar A, Yang C, de la Guardia M, Zhang W, Li X, et al. Proximal hyperspectral sensing of abiotic stresses in plants. Science of The Total Environment. 2023;861:160652. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang P, Yuan J, Yang P, Xiao F, Zhao Y. Nondestructive detection of sunflower seed vigor and moisture content based on hyperspectral imaging and chemometrics. Foods. 2024;13(9):1320. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- d’Aquino L, Cozzolino R, Malorni L, Bodhuin T, Gambale E, et al . Light Flux Density and Photoperiod Affect Growth and Secondary Metabolism in Fully Expanded Basil Plants. Foods. 2024;13(14):2273. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qin J, Monje O, Nugent MR, Finn JR, O’Rourke AE, et al . A hyperspectral plant health monitoring system for space crop production. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2023;14:1133505. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han P, Zhai Y, Liu W, Lin H, An Q, et al. Dissection of hyperspectral reflectance to estimate photosynthetic characteristics in upland cotton (Gossypium Hirsutum L.) under different nitrogen fertilizer application based on machine learning algorithms. Plants. 2023;12(3):455. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng Z, Yan P, Chen Y, Cai J, Zhu F. Increasing crop yield using agriculture sensing data in smart plant factory. InInternational Conference on Security, Privacy and Anonymity in Computation, Communication and Storage 2020 (pp. 345-356). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Han X, Yang J. Selection of optimal spectral features for leaf chlorophyll content estimation. Scientific Reports. 2024;14(1):25598. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Patricio M, Camas-Anzueto JL, Sanchez-Alegría A, Aguilar-González A, Gutiérrez-Miceli F, et al. Optical method for estimating the chlorophyll contents in plant leaves. Sensors. 2018;18(2):650. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye X, Kitaya M, Abe S, Sheng F, Zhang S. A new small-size camera with built-in specific-wavelength LED lighting for evaluating chlorophyll status of fruit trees. Sensors. 2023;23(10):4636. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheneamer AM, Halawi MH, Al-Qahtani MH. A hybrid human recognition framework using machine learning and deep neural networks. Plos one. 2024;19(6):e0300614. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moriyuki S, Fukuda H. High-throughput growth prediction for Lactuca sativa L. seedlings using chlorophyll fluorescence in a plant factory with artificial lighting. Frontiers in plant science. 2016;7:394. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang P, Li D. EPSA-YOLO-V5s: A novel method for detecting the survival rate of rapeseed in a plant factory based on multiple guarantee mechanisms. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture. 2022;193:106714. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jiang Y, Li B, Xu Y, Song H, et al. Accelerated photonic design of coolhouse film for photosynthesis via machine learning. Nature Communications. 2025;16(1):1396. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeng Y, Wang X, Jiang L, Qi JW, Lin Z, et al, He S. Fast multispectral imaging via hybrid-encoded LED illumination and a lightweight deep-learning model. Optics Letters. 2025;50(19):6177-80. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Acosta M, Quiñones A, Munera S, de Paz JM, Blasco J. Rapid prediction of nutrient concentration in citrus leaves using vis-NIR spectroscopy. 2023;23(14):6530. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohagheghi A, Moallem M. Measuring Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density in the Blue and Red Spectrum for Horticultural Lighting Using Machine Learning Methods. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement. 2023;73:1-0. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabzi S, Abbaspour-Gilandeh Y, Javadikia H. Machine vision system for the automatic segmentation of plants under different lighting condition Biosystems Engineering. 2017;161:157-73. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Laužikė K, Sirgedaitė-Šėžienė V, Uselis N, Samuolienė G. The impact of stress caused by light penetration and agrotechnological tools on photosynthetic behavior of apple trees. Scientific Reports. 2020;10(1):9177. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pourdarbani R, Sabzi S, Hernández-Hernández M, Hernández-Hernández JL, Gallardo-Bernal I, et al. Non-destructive estimation of total chlorophyll content of apple fruit based on color feature, spectral data and the most effective wavelengths using hybrid artificial neural network—imperialist competitive algorithm. 2020;9(11):1547. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pandey P, Ge Y, Stoerger V, Schnable JC. High throughput in vivo analysis of plant leaf chemical properties using hyperspectral imaging. Frontiers in plant science. 2017;8:1348. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang A, Li W, Men X, Gao B, Xu Y, et al. Vegetation detection based on spectral information and development of a low‐cost vegetation sensor for selective spraying. Pest Management Science. 2022;78(6):2467-76. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang D, Zou J, Luo S, Liu W, Li Y, et al. Study on uniformity and thermal stability of strip LED lamps in pea growing applications. Measurement. 2025;245:116604. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sarić R, Nguyen VD, Burge T, Berkowitz O, Trtílek M, et al. Applications of hyperspectral imaging in plant phenotyping. Trends in plant science. 2022;27(3):301-15. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mertens S, Verbraeken L, Sprenger H, De Meyer S, Demuynck K, et al. Monitoring of drought stress and transpiration rate using proximal thermal and hyperspectral imaging in an indoor automated plant phenotyping platform. Plant Methods. 2023;19(1):132. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lymperopoulos P, Msanne J, Rabara R. Phytochrome and phytohormones: working in tandem for plant growth and development. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2018;9:1037. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hadj Abdelkader O, Bouzebiba H, Pena D, Aguiar AP. Energy-efficient IoT-based light control system in smart indoor agriculture. Sensors. 2023;23(18):7670. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wessler CF, Weiland M, Einfeldt S, Wiesner-Reinhold M, Schreiner M, et al. The effect of supplemental LED lighting in the range of UV, blue, and red wavelengths at different ratios on the accumulation of phenolic compounds in pak choi and swiss chard. Food Research International. 2025 ;200:115438. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Munser L, Sathyanarayanan KK, Raecke J, Mansour MM, Uland ME, et al. Precise and Continuous Biomass Measurement for Plant Growth Using a Low-Cost Sensor Setup. Sensors. 2025;25(15):4770. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nam S, van Iersel MW, Ferrarezi RS. Biofeedback control of photosynthetic lighting using real‐time monitoring of leaf chlorophyll fluorescence. Physiologia Plantarum. 2025;177(1):e70073. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang Q, Zhao X, Zhao T, Li W, Ye J, et al . A machine-learning–powered spectral-dominant multimodal soft wearable system for long-term and early-stage diagnosis of plant stresses. Science Advances. 2025;11(26):eadw7279. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhao YR, Yu KQ, Li XL, He Y. Study on SPAD visualization of pumpkin leaves based on hyperspectral imaging technology. Spectroscopy and Spectral Analysis. 2014;34(5):1378-82.[Google Scholar]

- Farhangi H, Mozafari V, Roosta HR, Shirani H, Farhangi S, et al. Optimizing LED lighting spectra for enhanced growth in controlled-environment vertical farms. Scientific Reports. 2025;15(1):30152. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohmed G, Heynes X, Naser A, Sun W, Hardy K, et al. Modelling daily plant growth response to environmental conditions in Chinese solar greenhouse using Bayesian neural network. Scientific Reports. 2023;13(1):4379. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bian L, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Li L, Zhang Y, et al. A broadband hyperspectral image sensor with high spatio-temporal resolution. Nature. 2024;635(8037):73-81. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cai H, Zhou Q, Liu Y, Ma H, Sun Y, et al. Effects of nighttime LED supplementary lighting on growth, ovarian development and serum hormone levels of Acipenser gueldenstaedtii in flow-through system. Aquaculture. 2025;596:741757. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhong Z, Bai R, et al. Full-time sequence assessment of okra seedling vigor under salt stress based on leaf area and leaf growth rate estimation using the YOLOv11-HSECal instance segmentation model. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2025;16:1625154. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Karimzadeh S, Chavanapanit A, Moghimi A, Ahamed MS. Detection of Calcium Deficiency in Indoor-Grown Lettuce under LED Lighting using Computer Vision. Smart Agricultural Technology. 2025:101144. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P, Mondal TG, Shi Z, Afsharmovahed MH, Romans K, et al. Early detection of pipeline natural gas leakage from hyperspectral imaging by vegetation indicators and deep neural networks. Environmental Science & Technology. 2024;58(27):12018-27. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arcel MM, Yousef AF, Shen ZH, Nyimbo WJ, Zheng SH. Optimizing lettuce yields and quality by incorporating movable downward lighting with a supplemental adjustable sideward lighting system in a plant factory. PeerJ. 2023;11:e15401. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Shi M, Yang B, Ren J, Wang Q, et al. Glass-Microsphere-Encapsulated Long afterglow Phosphors Enhance Turfgrass Growth Under Low-Light Stress. Ceramics International. 2025. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Huang H, Shi M, Xiong Y, Wang J, et al. Optimized Spectral and Spatial Design of High-Uniformity and Energy-Efficient LED Lighting for Italian Lettuce Cultivation in Miniature Plant Factories. Horticulturae. 2025;11(7):779. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Hu J, Wang Z, Huang T, Xiang Y, et al. Pre-harvest nitrogen limitation and continuous lighting improve the quality and flavor of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) under hydroponic conditions in greenhouse. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2022;71(1):710-20. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou X, Zhao C, Sun J, Yao K, Xu M. Detection of lead content in oilseed rape leaves and roots based on deep transfer learning and hyperspectral imaging technology. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2023;290:122288. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zou J, Luo S, Shi M, Wang D, Liu W, et al. Effects of different light intensities on lettuce growth, yield, and energy consumption optimization under uniform lighting conditions. PeerJ. 2025;13:e19229. [Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zou J, Wang Z, Huang H, Huang X, Shi M. A Low-Energy Lighting Strategy for High-Yield Strawberry Cultivation Under Controlled Environments. Agronomy. 2025;15(5):1130. [Crossref] [Google Scholar]